10 Attachment Style Questionnaire Scientists Use to Measure Attachment Styles

Published on March 23, 2021 Updated on August 22, 2023

Have you ever wondered how attachment styles are measured? Whether the test you are completing is actually reliable? Whether you’ll get your real result? If you have, you’re definitely right to be cautious, and maybe even a bit skeptical, when taking free online attachment style tests.

Developing an accurate Attachment Style Questionnaire is not easy

Scientists spend years developing, testing, and validating their measurements. Unfortunately, not all tests offered online (and for free) are actually backed up by science.

And that’s a big issue, especially when it comes to mental health matters. Getting a false or inaccurate result might be confusing, and even harmful, to people who are looking for psychological advice and support.

For these reasons, we’ve decided to share with you a bit about the science of attachment style tests. In this blog post, you’ll get an idea of how it all started and how attachment tests have developed over time.

You’ll also discover what scientists actually measure with an attachment quiz. As the title suggests, this article offers an overview of science-based and validated attachment style tests that researchers use in their studies.

Assessment of Attachment Style Differences: The Beginning

The idea of “measuring attachment” began with the work of Mary Ainsworth in the 1960s. With numerous studies of infant-mother dyads and the relationships within those dyads, Ainsworth’s work forms the foundation for the assessment of attachment differences.

Even though Ainsworth focuses primarily on infants’ – and not on adults’ – attachment patterns, her approach, theoretical framework, and coding system have been used as a basis for succeeding attachment style tests.

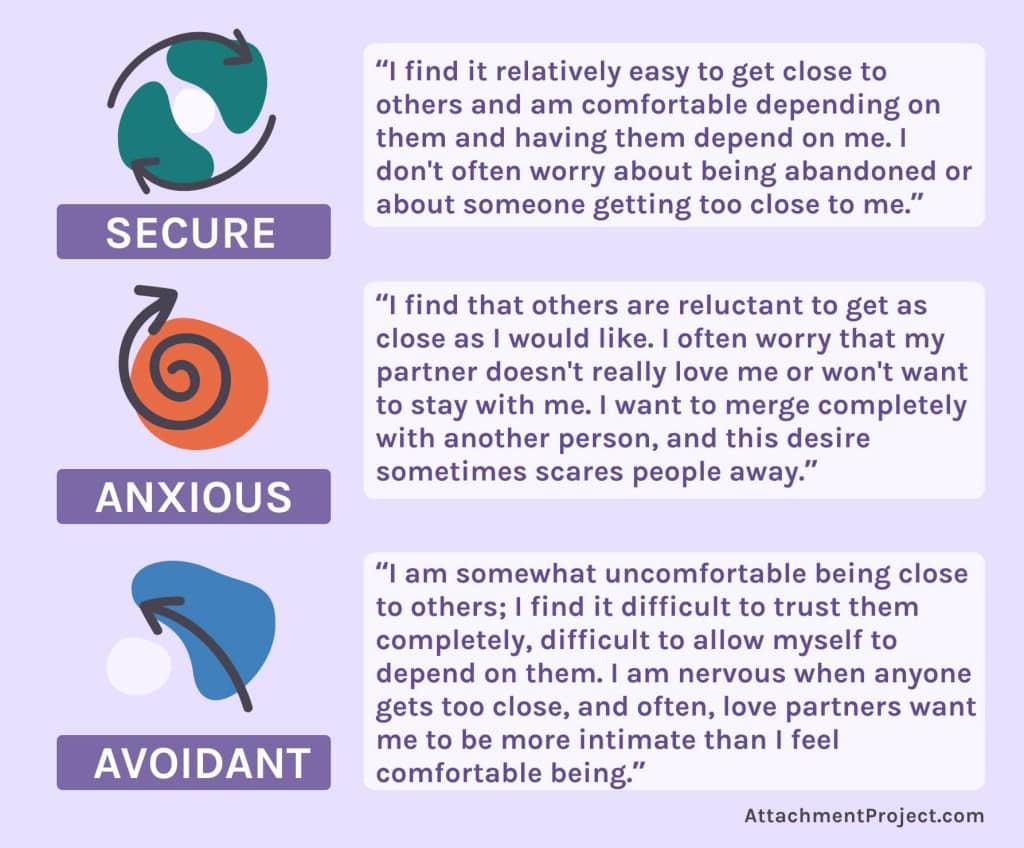

Adopting Ainsworth’s classification of three attachment patterns – secure, anxious, and avoidant – Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver come up with their attachment prototype framework. [1] [2]

They formulate three short descriptions of behaviors in romantic relationships (each one corresponds to one of the attachment patterns) and ask adults which description best depicts their past experiences in intimate relationships.

This type of measurement, however, does not allow researchers to take into account individual differences within each category (or prototype). To overcome this issue, future assessments utilize continuous scales to better illustrate each individual’s position within the different attachment categories.

10 Attachment Style Tests Used in Research

Over time, research on attachment measurement has grown and evolved tremendously. In the following section, we share with you 10 top-rated, validated, and widely used self-report attachment style tests.

1. Adult Attachment Questionnaire (AAQ)

Firstly, the AAQ is one of the questionnaires that deconstructs the attachment prototype descriptions into separate items. There are 17 items in total. AAQ classifies attachment patterns based on two dimensions – anxiety and avoidance. [2] [3]

The average scores on the avoidance and the anxiety scales are calculated to determine the individual’s avoidant attachment and attachment anxiety.

Even though this test is relatively old, the AAQ has been proven to be a valid and reliable measure of attachment avoidance and anxiety. [4] [5]

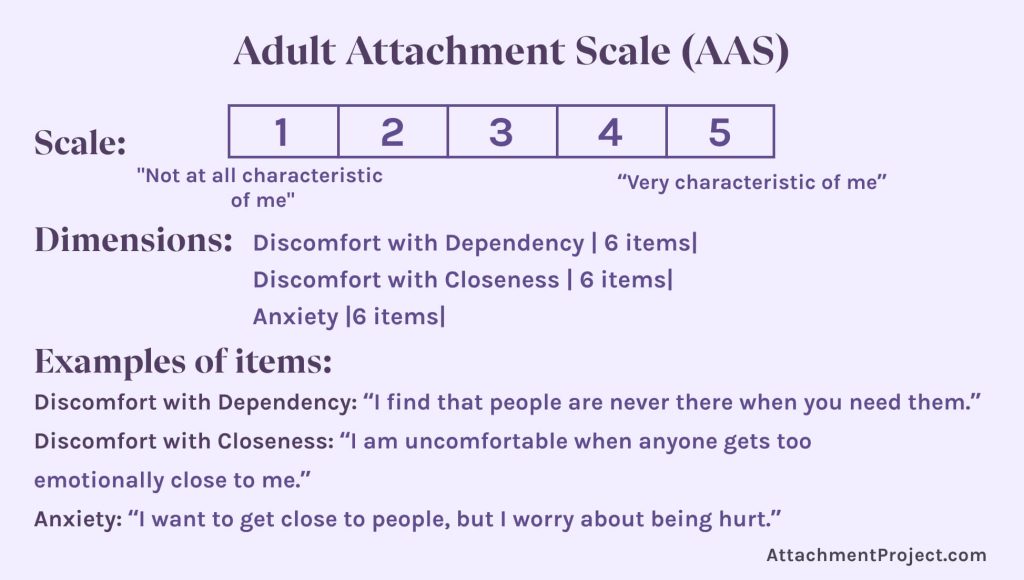

2. Adult Attachment Scale (AAS)

Similar to Simpson and colleagues (the creators of AAQ), Nancy Collins and Stephen Read also deconstruct the three attachment prototypes and formulate a test with 18 items in total. [3] [6]

A unique aspect of this attachment test is that the authors include additional items – measuring one’s perception of their partner’s availability and responsiveness as well as one’s reaction to separation from their partner.

Collins and Read outline three subscales of attachment: discomfort with closeness, discomfort with dependency, and anxiety about being rejected and abandoned. Results of the test are calculated based on the average score of the items in each of the three subscales. [6]

Unlike other measurements, the AAS contains two scales related to attachment avoidance. Even though both discomfort with closeness and dependency are highly correlated to attachment avoidance, the distinction between these two subscales is a unique feature of the AAS that might be quite useful, depending on the aim and context of the assessment. [7]

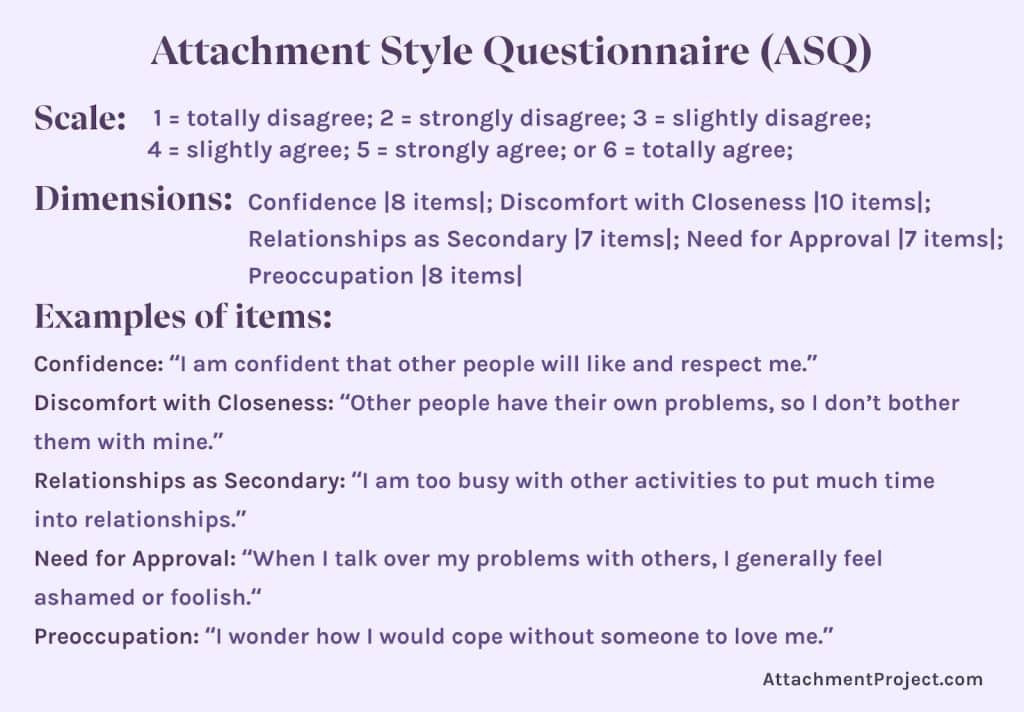

3. Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ)

The Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ) contains 40 items, the scores on which can be used in two ways. [8]

First, the ASQ outlines 5 subscales (see picture below), so the final test score can be used to represent where an individual stands regarding each of the five dimensions:

Second, the ASQ also allows the calculation of one’s attachment score on two general dimensions – avoidant attachment and attachment anxiety.

There are two main advantages of the ASQ. The first advantage is in the way the test is formulated. Unlike the previous tests we mentioned, the ASQ refers to close relationships, and not necessarily to intimate relationships.

This makes it suitable for younger individuals, who might not have much experience with romantic partners yet. The second benefit is that ASQ allows for a more precise assessment of specific facets of attachment avoidance or anxiety.

The ASQ has been tested in numerous studies and has been found to be a highly reliable and valid measure.

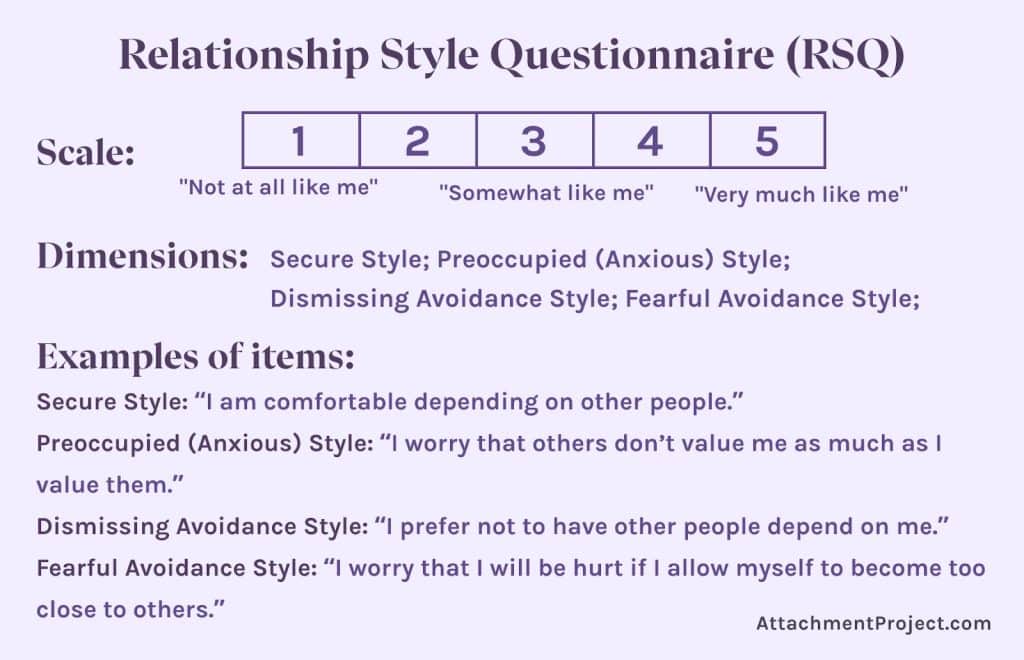

4. Relationship Style Questionnaire (RSQ)

![Taking into account Bowlby’s framework on internal working models, in 1990, Bartholomev [9] conceptualizes attachment styles in terms of one’s perception of self and one’s perception of others](https://149405263.v2.pressablecdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Frame-228-1024x911.jpg)

Taking into account Bowlby’s framework on internal working models, in 1990, Bartholomev conceptualizes attachment styles in terms of one’s perception of self and one’s perception of others (as depicted in the picture above). This results in the formation of four attachment prototypes (and not three, like in previous frameworks and assessments). [9]

A few years later, Griffin and Bartholomev develop the RSQ, which consists of 30 items. Attachment styles are calculated based on the average score of the items for each of the attachment categories. [10]

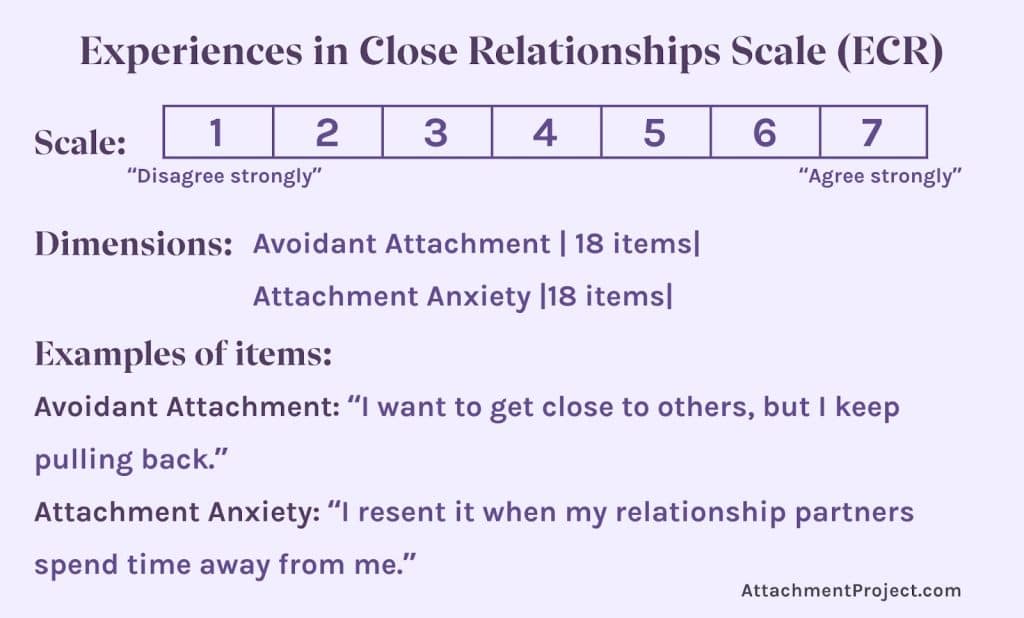

5. Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR)

The Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR) is probably the most known and used attachment styles test. It has been translated into 17 languages and used in hundreds of academic studies. [11]

In 1998, Brennan, Clark, and Shaver analyze all of the items used in attachment tests so far. As a result, they come up with two scales, each of which indicated one of the two attachment dimensions – attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety. [11]

The ECR test has demonstrated excellent scores on validity and reliability, which confirms that it’s a highly accurate measurement of one’s attachment style. In addition, ECR can be used in a wide range of contexts. ECR has been shown to assess attachment styles adequately among various groups – young adolescents, older adults, homosexual individuals, psychiatric patients, etc. [5]

6. ECR-R Items

The ECR-R Items (“R” for “revised”) is a revised version of the ECR questionnaire, in which some of the items have been replaced. The general outline and system of the test, however, is the same. The anxiety and avoidance scales in these two versions of ECR are highly correlated and seem to show similar results across studies. Similar to ECR, ECR-R Items demonstrates high validity and reliability. [12]

ECR: Short Versions

Due to its wide popularity, ECR has also been recreated in several shorter versions. The reason for that was that adding a 36-item questionnaire to the other measurements in a study would often result in a time-consuming and possibly exhausting (for participants) testing.

7. Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR)—Short Version

8. ECR-12: A Brief Version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR)

Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR)—Short Version and the ECR-12: A Brief Version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR) are two short versions of ECR that consist of 12 items, rated on a 7-point scale (identical to ECR). [13] [14]

Attachment avoidance and anxiety are calculated based on the average scores of the 6 avoidance items and 6 anxiety items.

Both of these questionnaires have shown high reliability. Still, ECR-12 has been tested in various relationship contexts (same-sex couples, disturbed couples, etc.) and could be considered a slightly better option than ECR-Short Version. [5]

ECR: Situational and Relationship-Specific Versions

Two more versions of ECR are worth mentioning when it comes to attachment style tests.

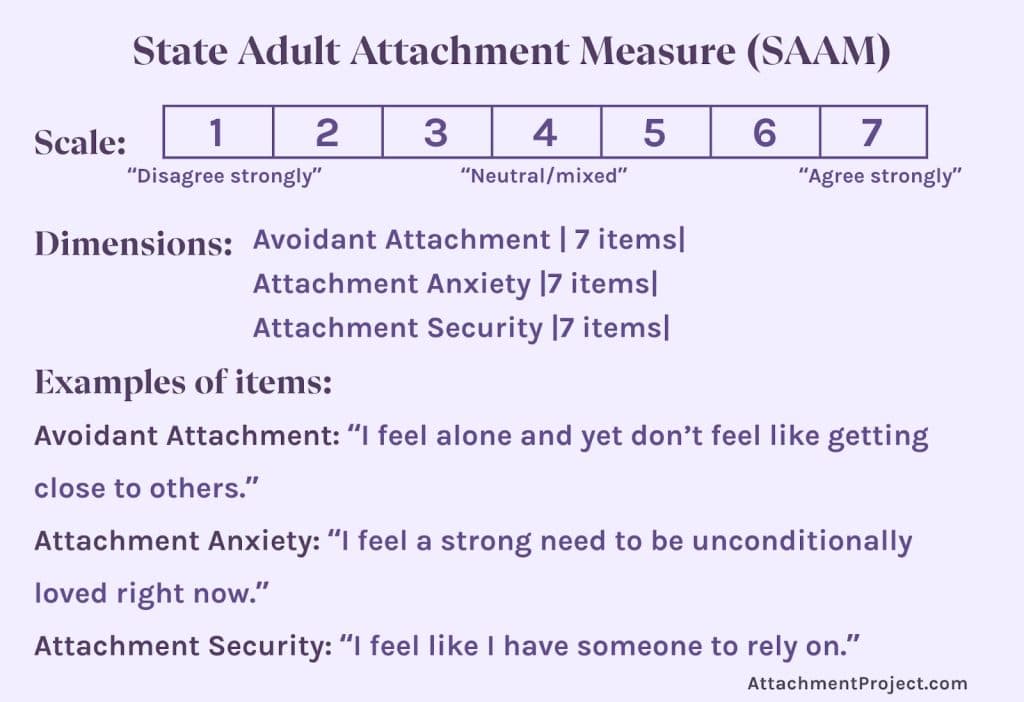

9. State Adult Attachment Measure (SAAM)

SAAM places an emphasis on the individual’s state in the present moment. Instead of referring to previous relationships, or relationship history, one reports the emotions they experience in the current moment. [15]

Therefore, SAAM is able to depict one’s temporary and contextual attachment patterns. SAAM is also suitable (and better than ECR for assessing an individual’s attachment-related changes over time. [16])

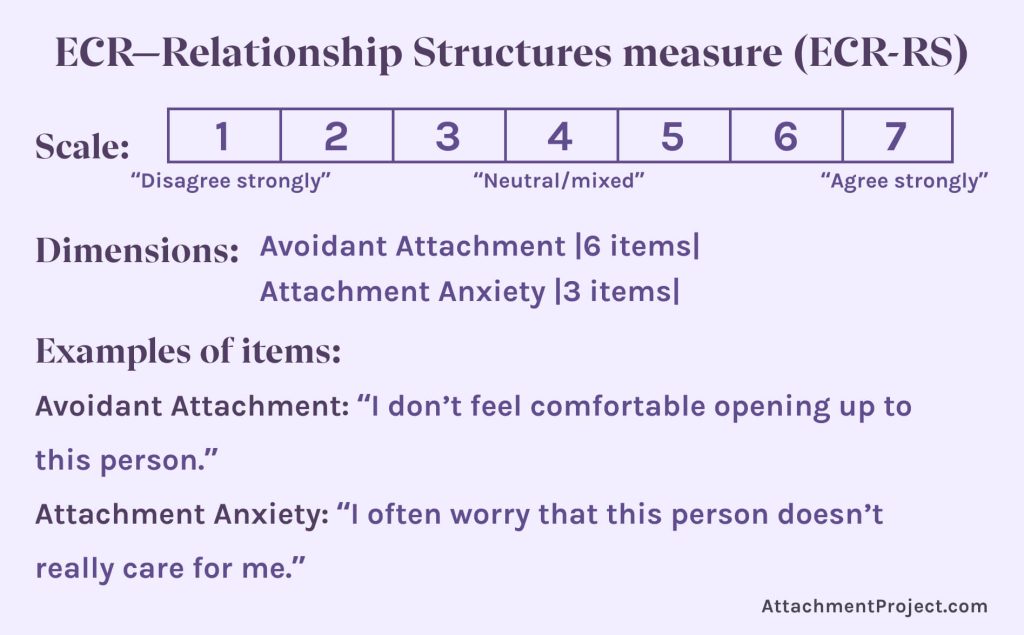

10. ECR—Relationship Structures measure (ECR-RS)

Lastly, ECR-RS is designed to assess attachment patterns across various relationship contexts. [17] Indeed, it has been proven to be a reliable measure, and even better than ECR, when it comes to addressing attachment patterns that are specific to a particular relationship (mother, father, friend, partner).

The ECR-RS contains 9 items selected from ECR. Individuals answer those same 9 items four times – referring to the relationships with their mothers (or mother-like figures), fathers (or father-like figures), best friends, and romantic partners. Attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety scales are calculated separately for each relationship.

*The ECR-RS is included in our Attachment Style Quiz. Click here to take the test and get your attachment style report for free!*

Are self-report tests the best option for attachment style assessment?

The measurements described in this article all have a valuable contribution to the field of attachment assessment. They have been used in hundreds of academic studies and have demonstrated a good level of accuracy and reliability.

It should be noted, however, that attachment self-report tests (in general) do have some disadvantages compared to attachment interviews.

Criticism towards self-report tests revolves around several aspects.

In short, researchers have argued that self-report tests are subjective, cannot measure the unconscious factors of attachment, are not based on individuals’ rich narrative (about unique memories, experiences, and history), do not depict the role of childhood experiences in attachment-related differences, etc. [5]

Similarly, we believe that attachment interviews with trained therapists can give people a better picture of the functioning of their attachment system.

Self-report tests are a great start for someone who’d like to get an idea of where they stand on the attachment anxiety and avoidance scales. Still, for those who suspect they might have serious attachment disturbances or are simply curious to dive into exploration of their attachment styles, the self-report test might not be enough.

BONUS: Two Questionnaires Related to Attachment

If you’re interested in your attachment style, you might also be curious to discover more about how well your caregiving and sexual systems function.

The two tests listed below measure those aspects. These questionnaires are not designed to assess your attachment style, but they are closely related to the topic.

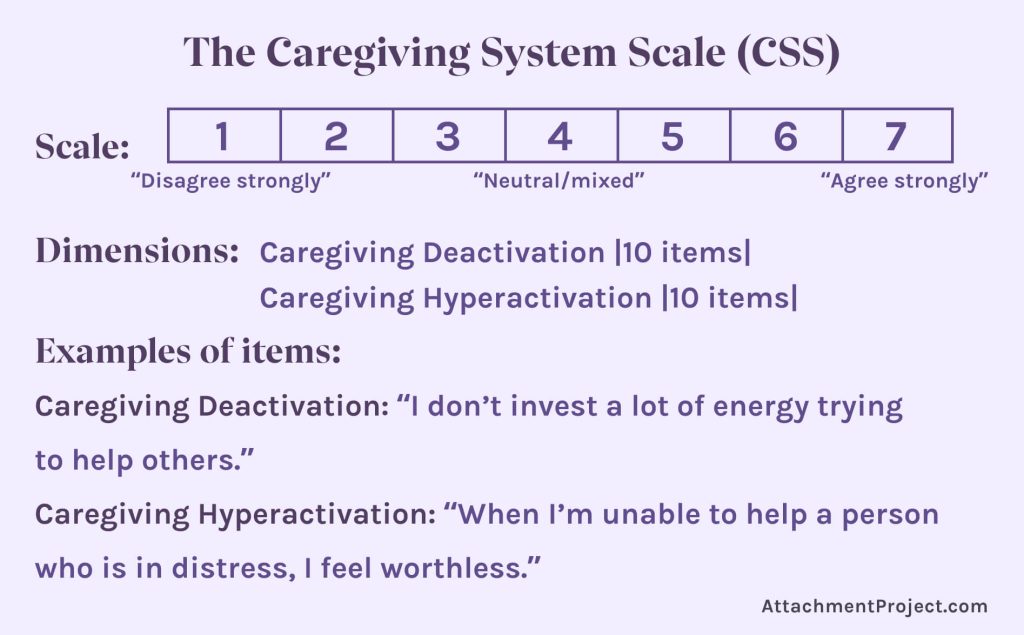

The Caregiving System Scale (CSS)

CSS is a validated and reliable measure of non-optimal functioning of one’s caregiving system. [18] Our caregiving system is what causes us to protect our loved ones from suffering and in times of danger and to support and encourage our loved ones to explore, grow, and develop. [19]

When the caregiving system is hyperactivated, we become hypervigilant to the needs of others and over-exaggerate those needs.

In other words, we put the needs of others (real or imagined) before our own, and we self-sacrifice. [5] This behavior resembles that of people with an anxious-preoccupied attachment style.

When the caregiving system is deactivated, we become insensitive and unresponsive to the needs of others.

Even when the people we love need closeness and assistance, we keep our emotional distance, lack empathy, and remain relatively uninvolved. [5] The deactivation of the caregiving system is thus closely related to attachment avoidance.

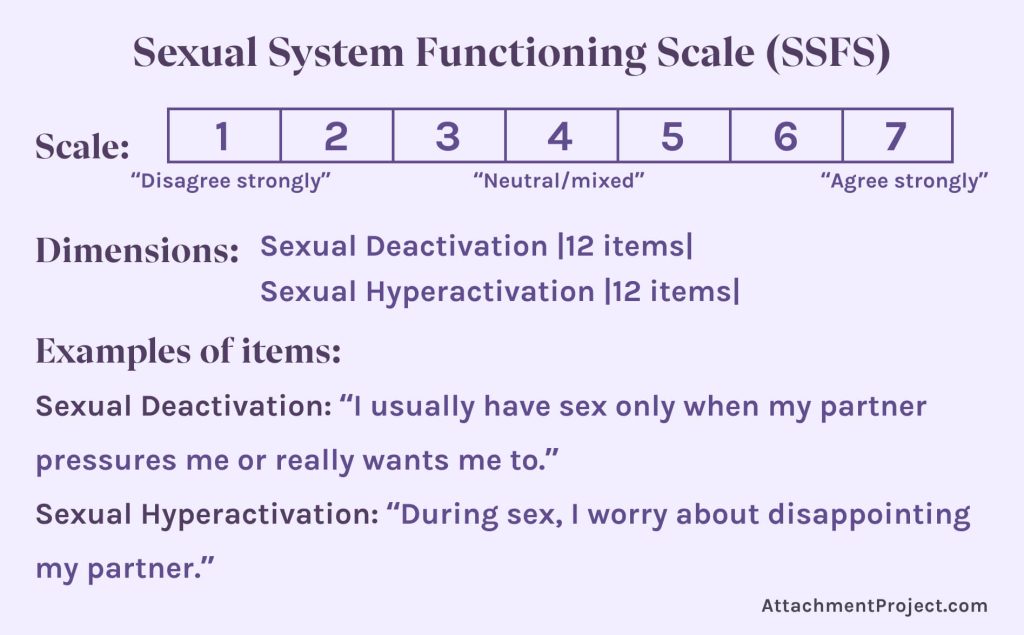

Sexual System Functioning Scale (SSFS)

Our sexual behaviors are closely linked to and influenced by our attachment styles. To measure the functioning of an individual’s sexual system, Birnbaum and colleagues designed the Sexual System Functioning Scale (SSFS). [20]

Sexual hyperactivation is characterized by preoccupation with the importance of sex as well as with the partner’s interest, reactions, signals, and needs related to sexual activities. [21]

It’s also related to intrusive worries about one’s attractiveness, ability to satisfy the partners, etc. This behavior is similar to the sexual behaviors exhibited by anxious-preoccupied adults. [21]

Sexual deactivation, on the other hand, is characterized by suppressing sexual needs and desires, disregarding the importance of sex and the partner’s sexual needs, and avoiding physical intimacy. [21] This pattern resembles the sexual behaviors of avoidant adults.

Knowing your attachment style is the first step to healing attachment-related issues.

If you’re struggling with relationships and suspect that you might have an insecure attachment style, taking a validated and reliable self-report test is definitely a good start.

It’s important, however, to keep in mind that not every test you find online is adequate and will give you your real result. Besides, self-report attachment style tests are not as accurate as interviews conducted by trained professionals.

So, even if you take a reliable test, like the one we offer on our website, you could also consider making an appointment with a therapist trained to conduct and score the AAI (Adult Attachment Interview).

Prefer to start with an online Attachment Style Quiz? Complete the ECR-RS anonymously and get your attachment style report completely FREE!

Resources:

[1] Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: Assessed in the Strange Situation and at home. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

[2] Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511–524.

[3] Simpson, J. A., Rholes, S. W., & Phillips, D. (1996). Conflict in close relationships: An attachment perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(5), 899–914.

[4] Graham, J. M., & Unterschute, M. S. (2015). A reliability generalization meta-analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97(1), 31–41.

[5] Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (Second Edition). Guilford Press.

[6] Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 644–663.

[7] Collins, N. L. (1996). Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(4), 810–832.

[8] Feeney, J. A., Noller, P., & Hanrahan, M. (1994). Assessing adult attachment. In M. B. Sperling & W. H. Berman (Eds.), Attachment in adults: Clinical and developmental perspectives (p. 128–152). Guilford Press

[9] Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal relationships, 7(2), 147-178.

[10] Griffin, D. W., & Bartholomew, K. (1994). The metaphysics of measurement: The case of adult attachment. In K. Bartholomew & D. Perlman (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships: Attachment processes in adulthood (Vol. 5, pp. 17–52). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Self Report Measurement

[11] Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (p. 46–76). The Guilford Press.

[12] Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 350– 365.

[13] Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR)—short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(2), 187–204.

[14] Lafontaine, M.-F., Brassard, A., Lussier, Y., Valois, P., Shaver, P. R., & Johnson, S. M. (2015). Selecting the best items for a short-form of the Experiences in Close Relationships questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. Advance online publication.

[15] Gillath, O., Hart, J., Noftle, E. E., & Stockdale, G. D. (2009). Development and validation of a state adult attachment measure (SAAM). Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 362–373.

[16] Xu, J. H., & Shrout, P. E. (2013). Assessing the reliability of change: A comparison of two measures of adult attachment. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(3), 202–208.

Attachment in Relationships

[17] Fraley, R. C., Heffernan, M. E., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2011). The Experiences in Close Relationships—Relationship Structures questionnaire: A method for assessing attachment orientations across relationships. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 615–625.

[18] Shaver, P. R., Mikulincer, M., & Shemesh-Iron, M. (2010). A Behavioral systems perspective on prosocial behavior. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature (pp. 73–92). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

[19] Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Gillath, O. (2008). A behavioral systems perspective on compassionate love. In B. Fehr, S. Sprecher, & L. G. Underwood (Eds.), The science of compassionate love: Research, theory, and application (pp. 225–256). Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

[20] Birnbaum, G. E., Mikulincer, M., Szepsenwol, O., Shaver, P. R., & Mizrahi, M. (2014). When sex goes wrong: A behavioral systems perspective on individual differences in sexual attitudes, motives, feelings, and behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(5), 822–842.

[21] Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2008). Augmenting the sense of security in romantic, leader–follower, therapeutic, and group relationships: A relational model of psychological change. In J. P. Forgas & J. Fitness (Eds.), Social relationships: Cognitive, affective, and motivational processes (pp. 55–74). New York: Psychology Press.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox