What is Limerence and How to Overcome It

A new romantic interest can be exciting, even thrilling – but do you ever find yourself so caught up in your potential relationship with this person that thinking about it distracts you from everyday life? If this sounds familiar, you may be experiencing limerence.

Limerence isn’t a diagnosis, but it does come with strong, difficult feelings, so understanding what it is and why it might happen can help us to understand what we’re experiencing. In this article, we’ll talk about where the concept of limerence comes from, signs you might be in limerence, the stages of limerence, and how you might be able to overcome limerence and return to approaching potential new relationships in a healthy way.

What is Limerence?

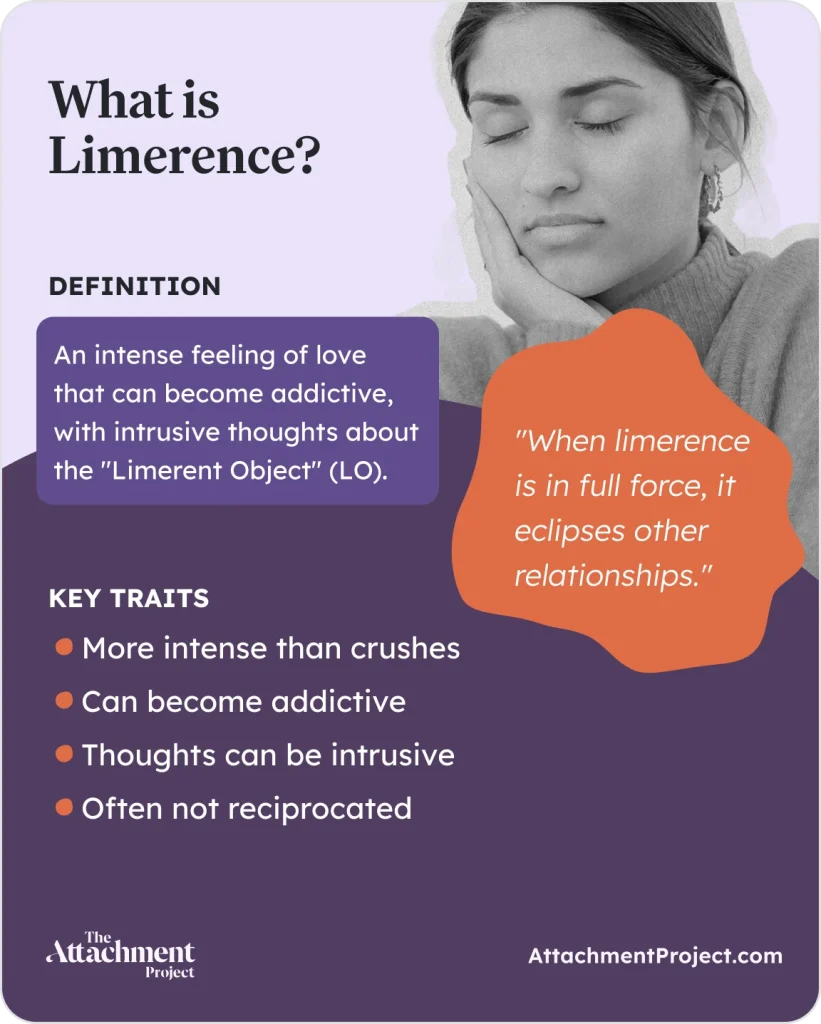

“Limerence” was first coined by psychologist Dorothy Tennov in 1979 to describe a particular experience of love1. She had noticed that love could be experienced in many different ways, and the state of “being in love” could sometimes be so intense that it might be seen as negative. So, she used the word “limerence” to describe an intense feeling of love for someone, separate but sometimes coinciding with care, affection, and/or sexual attraction for them.

“Limerence is not in any way preeminent among types of human attractions or interactions; but when limerence is in full force, it eclipses other relationships.”

– Dorothy Tennov, 1979.

Later research built on Tennov’s ideas, further distinguishing limerence from a crush or being in love. Researchers found that limerence is more intense to the extent that it can become addictive, and thoughts about the other person (also called the Limerent Object or LO) can even be intrusive2.

What Causes Limerence?

Lots of things can come into play to cause limerence, often described as “a perfect storm”3. Past or current life experiences, pre-existing mental health difficulties, and coincidental timing can all lead to limerence developing.

Attachment styles and childhood experience could also have an influence on the development of limerence (we’ll dive deeper into limerence and attachment styles soon), and adult attachment disruptions such as relationship difficulties or bereavement may increase our vulnerability to limerence.

One study found that, in women, experiencing limerence was linked to lower self-esteem and lower sexual autonomy (measuring communication, empowerment, assertiveness, and responses to cultural norms in sexual contexts)4. Men and non-binary people were not part of this study, so we don’t know whether these results are exclusive to women or not.

Tennov theorized that limerence could have an evolutionary function: when the pursuit of an LO is successful, the result is commitment and reproduction, which passes down genes that could contribute to limerence. In other words, limerence might make you more likely to find a partner and start a family, and your children may inherit limerent tendencies.

For the time being, this is just a theory – we don’t yet know whether there’s an exact cause of limerence, but it seems to be a biological mechanism that kicks into gear when we’re vulnerable and feeling both hope and uncertainty about a potential love interest.

Limerence Symptoms

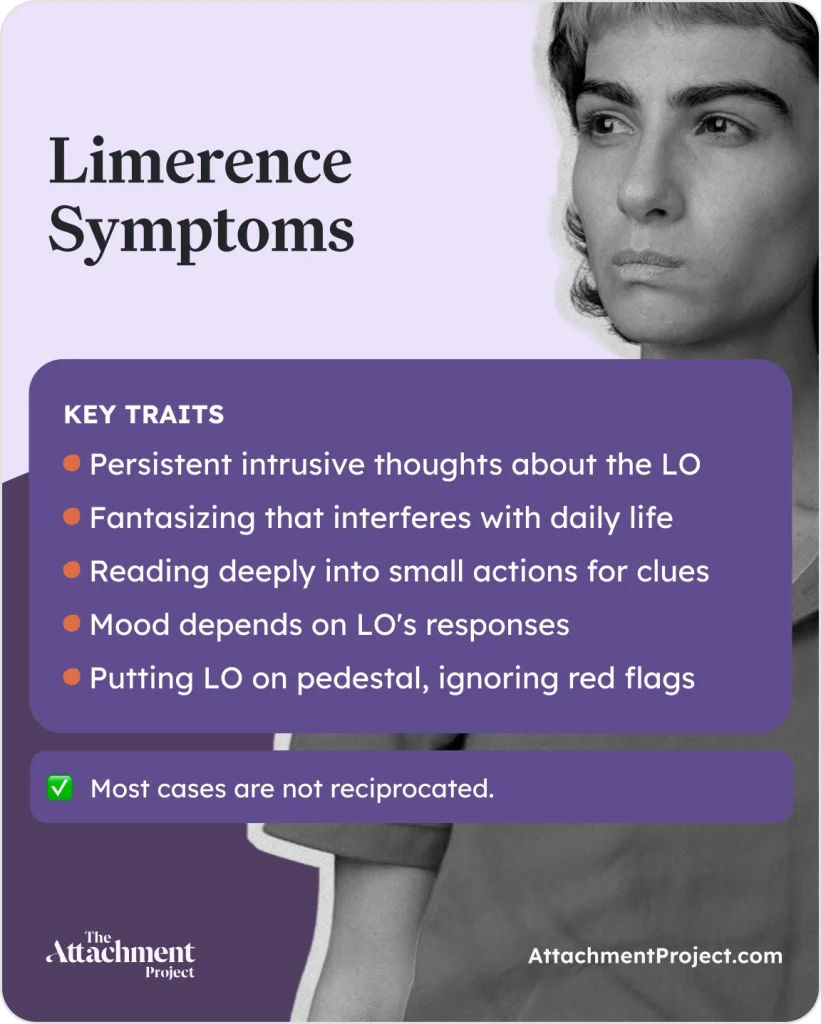

The key signs of limerence are:

- Persistent intrusive thoughts about the LO, such as constantly wondering what they’re up to or thinking about making contact with them. These thoughts can be so intrusive that it’s difficult to concentrate on other activities.

- Fantasizing about the LO, again to such an extent that it gets in the way of other things. Fantasies can be highly detailed and often involve reciprocated feelings.

- Reading deeply into small actions in a search for clues about the LO’s feelings, such as taking small gestures of kindness as confirmation that your feelings are reciprocated.

- Your mood is dependent on your interactions with your LO – when they go well you might feel like you’re “walking on air”, but perceived rejection can make you feel extremely low.

- You put your LO on a pedestal and ignore any red flags. You idealize them and may project or exaggerate positive traits, even if you might not know a lot about them.

Tennov found that in most cases, limerence was not reciprocated. Even in pairings where limerence was reciprocated, Tennov said that: “there is some lack of reciprocation in all limerent relationships, since limerence intensity continually wavers.”

The 5 Stages of Limerence

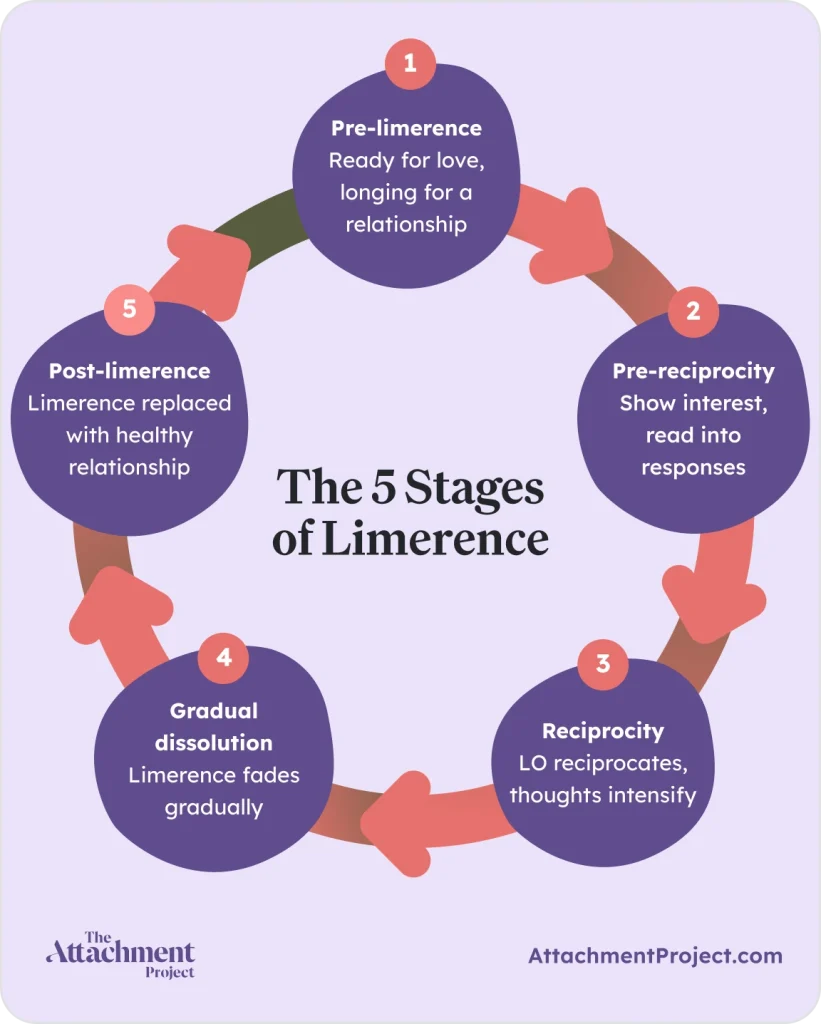

There are several different ways limerence has been conceptualized in stages. In this article, we’ll use Verhulst’s 5 stages5:

1. Pre-Limerence

During pre-limerence, you don’t yet have a particular love interest, but you feel ready for love and you might find yourself longing for a relationship. If somebody you’re interested in shows the potential to be interested in you, you might begin to develop limerence for them.

2. Pre-Reciprocity

In pre-reciprocity, you might start to subtly show interest in your LO. You may try to gauge their interest without being direct, which results in a need to read into their responses. If you perceive that they’re rejecting your advances, you might be extremely upset. This feeling gradually goes away until limerence returns, at which point, you may interpret no clear rejection as a sign they feel the same way.

3. Reciprocity

If the LO reciprocates, you might find your thoughts of them intensify for days to years. Since limerence relies on both hope and uncertainty, the length of the reciprocity stage can depend on the nature of your relationship – if you feel more secure, you might experience a shorter reciprocity stage. However, the dissolution of limerence doesn’t necessarily mean the absence of love or physical desire in your relationship.

4. Gradual Dissolution

As limerence gradually dissipates, it leaves room for a mature, healthy relationship to grow. However, it also leaves room for anxiety and distress, especially when it provided a distraction from other life events. You might long for the feeling of limerence to come back and look for blame or evidence of deception to explain their disappearance; this can be the downfall of limerent relationships.

5. Post-Limerence

In post-limerence, there is no trace of limerence left and no desire to return to it. In its place, a communicative and healthy relationship can blossom – as Tennov said, limerence is not the same as love or attraction, so both can still exist in the post-limerent stage. This stage is rarely achieved due to the emotional turbulence involved in limerent relationships.

What Are the Positive and Negative Effects of Limerence?

Limerence is an emotional rollercoaster, and the emotional highs can be full of joy, elation, and excitement. These feelings and obsessive limerent thoughts can help to distract us from other painful experiences, which – although not a recommended coping mechanism – does help us to get through difficult times.

Limerence can come with some other surprising upsides, as we might invest more time in self-improvement to impress our LO or explore hobbies and interests that we might not have explored otherwise. Even though our intention is to impress our LO, we might end up improving our own wellbeing through these experiences.

Yet, the emotional high does come with an inevitable low; if the LO does not reciprocate, you might experience extreme uncertainty, anxiety, and depression. It can be more difficult to eat or sleep and we may experience feelings of hopelessness, and potentially even suicidal thoughts or intentions.

Although limerence can lead to self-improvement, it can also get in the way of our other goals and hobbies. As the LO becomes our priority, we might put other relationships to the side. Obsessive thoughts about our LO can also distract us from work and study.

This intensity sets limerence apart from a regular crush – so how else can you tell the difference?

How Does Limerence Differ from a Healthy Crush?

Limerence might start out like any other healthy crush; both the early stages of limerence and a healthy crush typically involve feelings of hope and uncertainty. However, in a healthy crush, this uncertainty is typically resolved through expressing interest in the other person and this interest being either reciprocated or not.

In contrast, uncertainty in limerence doesn’t end. This limitless uncertainty leads to fantasizing, idealization, and sometimes impulsive behaviors. These can take over day-to-day life and get in the way of work, socializing, and even our downtime.

Limerence vs Love: What’s the Difference?

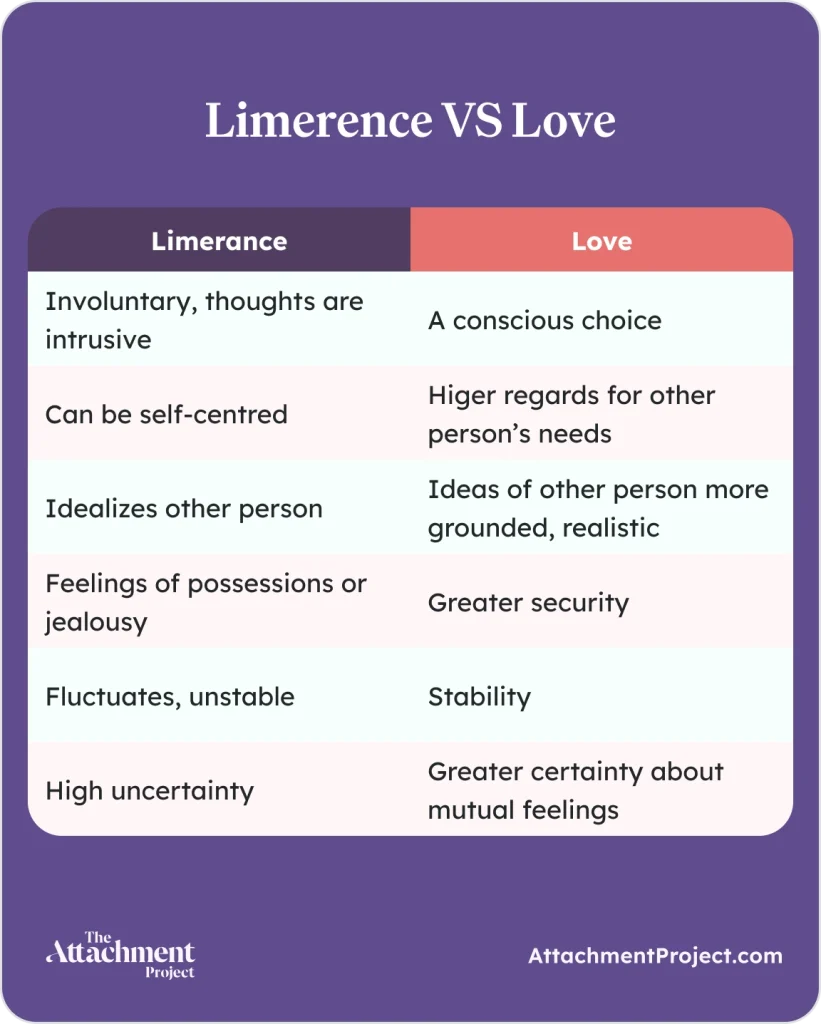

“Limerence” was defined to distinguish the feelings often associated with being in love from the act of love. While the feeling of being in love can be intense and, ironically, self-centred, the act of love involves choosing to prioritize, respect, and commit to another person.

While limerence has an involuntary feeling about it, to love is an active and conscious choice. When we love somebody, thinking about them might be enjoyable, but it doesn’t interrupt our daily life to the extent that we find it more difficult to function.

Loving somebody means seeing them for who they are, while, in limerence, we form idealized versions of LOs and imagine them as the perfect partner. We might also feel possessive over someone when in limerence, but experience a more stable, secure relationship when in love.

What Are the Signs Limerence Is Ending?

Since limerence primarily involves uncontrolled intrusive thoughts about the LO, the most obvious sign that limerence is ending is a decrease in these thoughts. You might gradually find it easier to focus on yourself again, have less strong emotional reactions to your LO, and even eat, sleep, and feel better overall.

Limerence can end with or without reciprocation from your LO – it might be replaced by love, a new LO, or simply personal growth as you invest more time in yourself again.

The end of limerence can be difficult, even if you want it to be over. You might miss the emotional highs, or have to deal with anything that limerence might have been helping to distract you from. This is normal, and okay. Try to replace time spent thinking about your LO with healthy coping mechanisms – talk to your friends or family, engage in active hobbies and interests (active activities are things that take cognitive effort like sports, games, or crafts, vs. passive activities like watching TV), and practice grounding or self-reflective activities like mediation or journaling.

Attachment Style and Limerence

Insecure attachment, specifically anxious attachment, shares many similarities with limerence. Anxious attachment results from inconsistent caregiving during childhood, which gives the child (and later the adult) an unbalanced sense of security in relationships.

In relationships, someone with an anxious attachment style experiences preoccupation with the relationship and their partner, is emotionally dependent, and has low self-esteem. They may base their self-esteem on the approval and acceptance of others, which creates a strong fear of rejection and failure to please their partner.

This is very similar to the profile of limerence, but there is a key difference between limerence and attachment anxiety: limerence is an attitude toward one specific person, while attachment anxiety is an attitude toward the world and others in general.

Nevertheless, some people who have experienced limerence do feel that their early attachment experiences played a role3. Some see limerence as a “direct re-enactment” of experiences of childhood abandonment that left them craving affection from others.

Even though limerence and anxious attachment styles might be connected, this doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone who experiences limerence has a generally anxious attachment style, or that everyone with an anxious attachment style is prone to limerence.

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

Is Limerence a Mental Disorder?

Limerence itself is not a diagnosis, although it has been compared with separation anxiety disorder, addiction, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

These comparisons are drawn primarily from the emotional distress, compulsive, and intrusive aspects of limerence. The core characteristics of OCD are6:

- Unwanted and recurring thoughts that cause anxiety

- Attempts to ignore or suppress these thoughts

- Repetitive behaviors or mental actions that you feel need to be done to reduce distress about or prevent the thought

- These behaviors impact daily functioning (and aren’t better explained by another diagnosis)

A couple of these might now sound very familiar. While limerence doesn’t necessarily include all 4, it is possible for thoughts about the LO to become so intense and distressing that OCD behaviors appear.

In addiction, addictive behaviors can result in extreme highs and lows. We can become so dependent on those highs that we find it difficult to avoid the behavior that causes them, even if we know it’s not good for us. In this way, there can be a compulsive element to these behaviors – even though we might not want to, we can feel so driven to find the high that we feel like we can’t resist it.

The same can happen in limerence, where we might know that avoiding the LO would be best for us but continue to seek reciprocation from them anyway as our brains search for the high of perceived confirmation.

Separation anxiety disorder is an OCD-related diagnosis involving intense distress at the separation from an attachment figure that’s prolonged, severe, and not appropriate for someone’s developmental stage – meaning that what’s not appropriate for an adult might be less concerning for a young child. Some researchers have suggested that separation anxiety disorder might overlap with limerence, especially when there’s marked separation from the LO3.

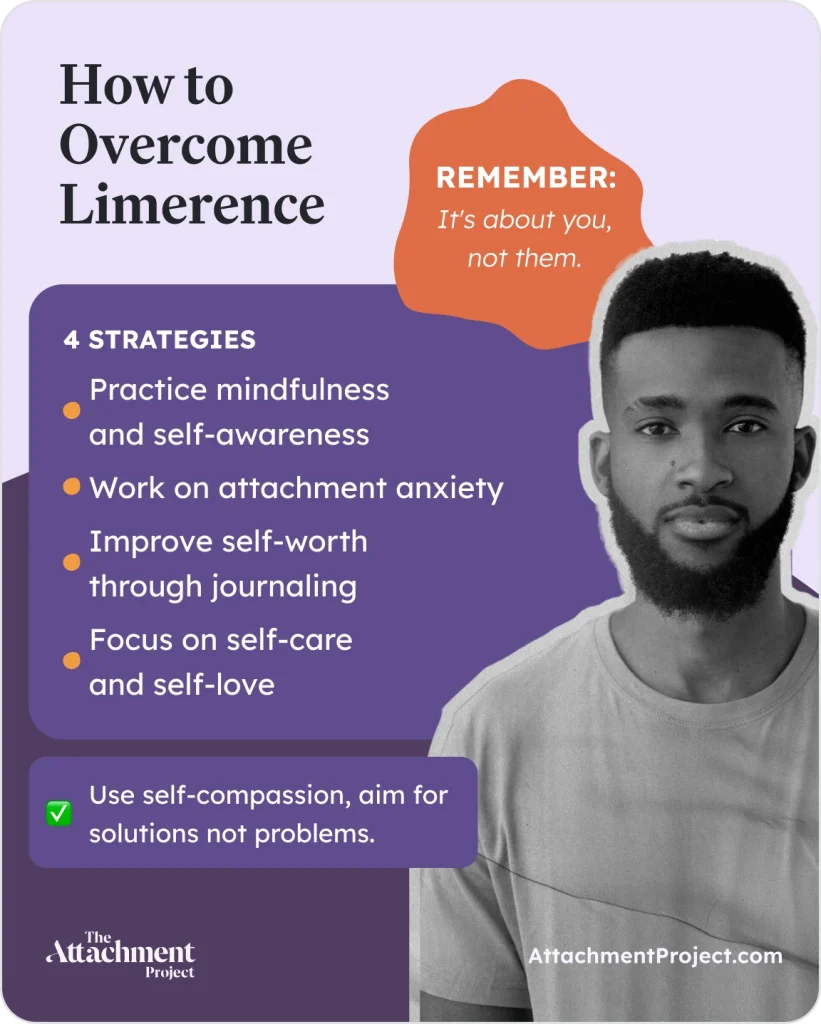

How to Overcome Limerence

Even though the limerence definition involves preoccupation with another person, remember that it isn’t about them: it’s about you. This might be your first time being in a state of limerence, or perhaps it happens to you frequently – either way, it’s important to be introspective and understand more about what need this attachment is filling.

The first step is to get into the right frame of mind and commit to the process of healing. Approach it from a place of self-compassion and understanding, with the aim of finding solutions rather than dwelling on the problem. Therapy may be a suitable route for you, but there are other things you can do to start to heal from limerence.

Practice Self-awareness/Mindfulness

Noticing our patterns of thoughts and behaviors is the first step toward positive change. When we’re aware of what’s happening within us, we can learn what our triggers are and intervene more effectively. Mindfulness practice can help us to pay more attention to our own minds – remember that mindfulness is a skill, and like any other skill, it takes practice. Try some guided mindfulness resources and have patience if it doesn’t work for you right away.

Work on Attachment Insecurities

If your limerence overlaps with general attachment anxiety, it may be helpful to work towards a more secure attachment style. The first step is knowing your attachment style – you can find yours using our free quiz.

Improve Self-worth

Since limerence is linked with low self-esteem, working on your self-worth could help to keep feelings of limerence at bay. You could practice improving self-esteem by engaging in hobbies and interests that you enjoy, spending more time with friends and family, or journalling using self-affirming prompts. These could be as simple as writing down 3 things you like about yourself or 3 achievements you’re proud of – it might feel strange at first, but the key is consistency.

Focus On Self-Care and Self-Love

Be kind to yourself – your brain is just doing its best to process its feelings, and there may be much more going on under the surface. Practice putting yourself first – for instance, if you don’t really want to go to a party but you know they’ll be there, consider making alternative plans to do something you’re more interested in. Remember that self-care isn’t always relaxing, and sometimes the best self-care is doing your best to make sure the work you need to do gets done with or without limerence as a distraction. Self-care can also look like asking for help when this is easier said than done.

LEARN HOW TO OVERCOME LIMERENCE

Conclusion

Although having a new potential connection in your life is fun and exciting, limerence can also make it incredibly stressful. While it can distract us from more difficult feelings, it’s helpful to be aware of what might really be going on within ourselves when we’re extremely focused on somebody else.

If you’re experiencing limerence without reciprocation, do your best to turn some of that energy toward yourself – how can you love, validate, and support yourself more day to day?

If you’re in a relationship with your LO and limerence is in the dissolution phase, remember that this is natural and nobody is to blame. In the space it leaves behind, you now have the opportunity to grow a more stable, emotionally mature relationship.

Although limerence can be challenging, it also gives us an opening to find out more about ourselves. Sometimes this could be a hobby we wouldn’t have tried otherwise, and sometimes it can be attachment processes we might not have been aware of before – sometimes, it can be even deeper. Wherever your limerence leaves you, remember to treat yourself with compassion and patience as you navigate these feelings.

Take our limerence test to gain deeper insight into your experience and start your journey toward emotional freedom.

FAQs about Limerence

What triggers limerence?

Limerence is triggered when we feel a mix of hope and uncertainty about a romantic interest. It can be preceded by current or past life events, attachment disruptions, mental health difficulties, and coincidental timing.

What does limerence feel like?

Limerence is the feeling we often refer to as “being in love”, although there are differences between love and limerence. In limerence, we feel an all-consuming need for the other person’s affection, and may think about them and depend on their reactions to an extent that interferes with daily life.

What are limerent tendencies?

According to Dorothy Tennov’s foundational research, the common limerent tendencies include obsessive fantasizing about the limerent object (LO), altering aspects of personality or looks to impress the LO, impulsive actions, idealization of the LO, mood swings, and withdrawal from friend groups and hobbies.

What does limerence mean?

Limerence means an intense longing for another person even when they don’t fully reciprocate. You may struggle to think about anything else but your “crush” and neglect other aspects of life like socializing, work, and other responsibilities.

References

- Tennov D. Love and limerence: The experience of being in love. Scarborough House; 1998 Dec 29.

- Bradbury P, Short E, Bleakley P. Limerence, hidden obsession, fixation, and rumination: A scoping review of human behaviour. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. 2024 Apr 25:1-0.

- Willmott L, Bentley E. Exploring the lived-experience of limerence: a journey toward authenticity. The Qualitative Report. 2015;20(1):20-38.

- Kim O, Jeon HO. Factors influencing limerence in dating relationships among female college students. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society. 2020;21(2):304-14.

- Verhulst J. Limerence: Notes on the nature and function of passionate love. Psychoanalysis & Contemporary Thought. 1984.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edn). APA, 2013.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox