The 4 Parenting Styles and Their Impact on Attachment: Which Parenting Style Are You?

Striking the right balance between warmth and boundaries is something many parents find difficult. You want the best for your child, and you know that raising them to be confident, wise, and emotionally intelligent requires both support and structure.

This is the framework that psychologist Diana Baumrind used to develop her theory of 3 parenting styles – later 4 parenting styles, with contributions from Eleanor Maccoby and John Martin1. This theory offers a broad introduction to parenting styles which you can use to kickstart your journey of self-discovery as a parent.

Parenting styles are an important part of attachment theory – your parents’ parenting styles impacted your attachment style, which will, in turn, impact your parenting style and the attachment bond you form with your child. We’ll explore this in more detail, along with a deep dive on Baumrind’s 4 parenting styles, the cultural variations of parenting styles, and whether you can change your parenting style.

To find out your own parenting style, take our free parenting styles quiz.

Understanding Parenting Styles: The Two Core Dimensions

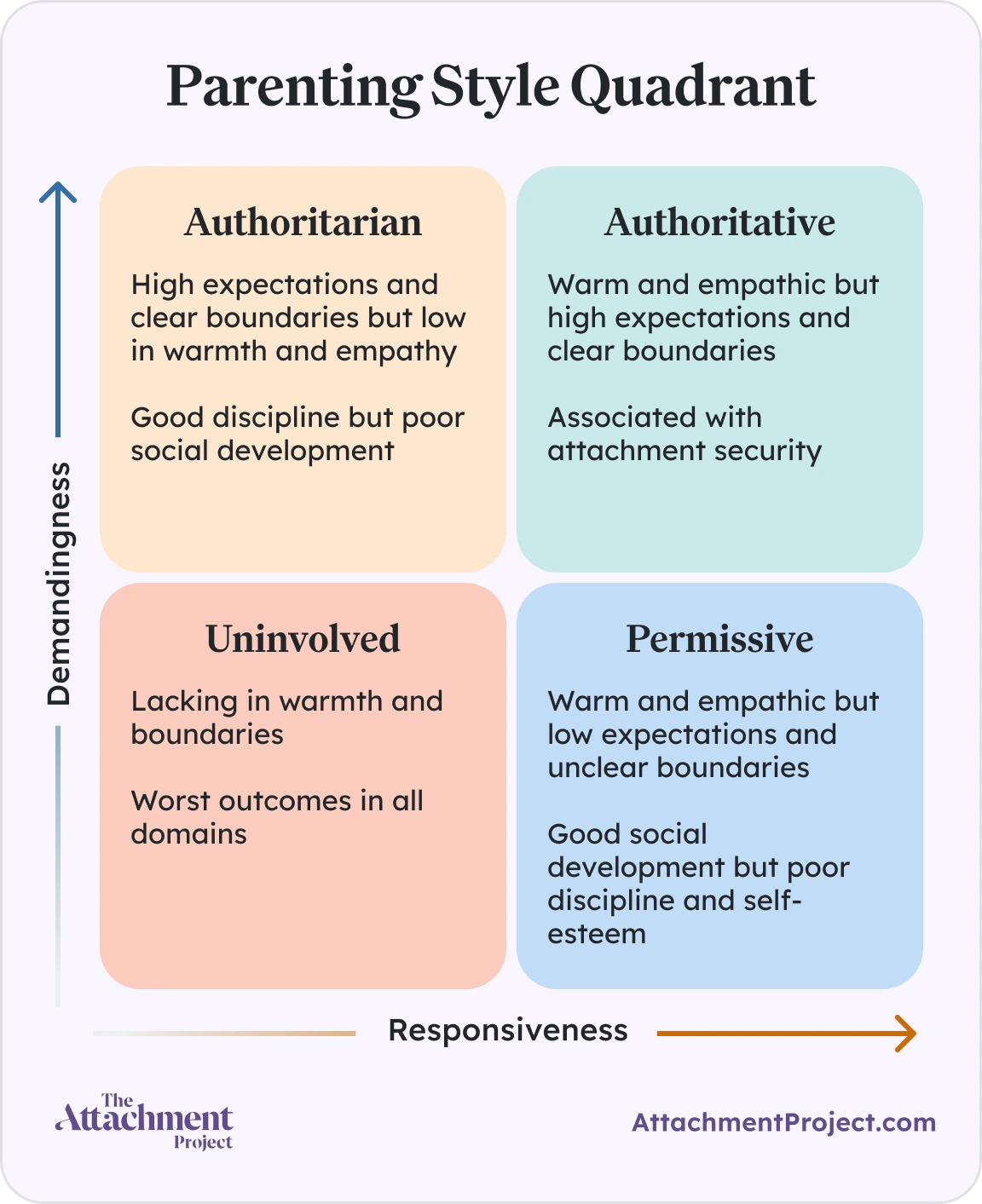

According to Baumrind, measures of responsiveness and demandingness are at the core of your parenting style. Maccoby & Martin turned this into a 2-dimensional model categorizing parenting on scales of responsiveness and demandingness, resulting in 4 possible categories.

Responsiveness is the degree to which you respond and are sensitive to your child’s emotional needs, while demandingness is the degree to which you exert control over your child.

The 4 different parenting styles in this model are:

- Authoritative Parenting – high responsiveness, high demandingness.

- Authoritarian Parenting – low responsiveness, high demandingness.

- Permissive Parenting – high responsiveness, low demandingness.

- Uninvolved Parenting – low responsiveness, low demandingness.

One limitation of this model is that it doesn’t account for the way our parenting styles might shift depending on the context or situation. It’s normal for our approaches to change, and domain-specific models of parenting help to explain in more detail how this might work – the 4 parenting styles described here can be considered very broad, general patterns, instead of overly strict categories3.

Authoritative Parenting: The Balanced Approach

Authoritative parenting, high in both demandingness and responsiveness, is often considered the best parenting style – although this is challenged and varied by cultural context. That is to say, the parenting style that we think is best is influenced by what’s considered normal in our own culture.

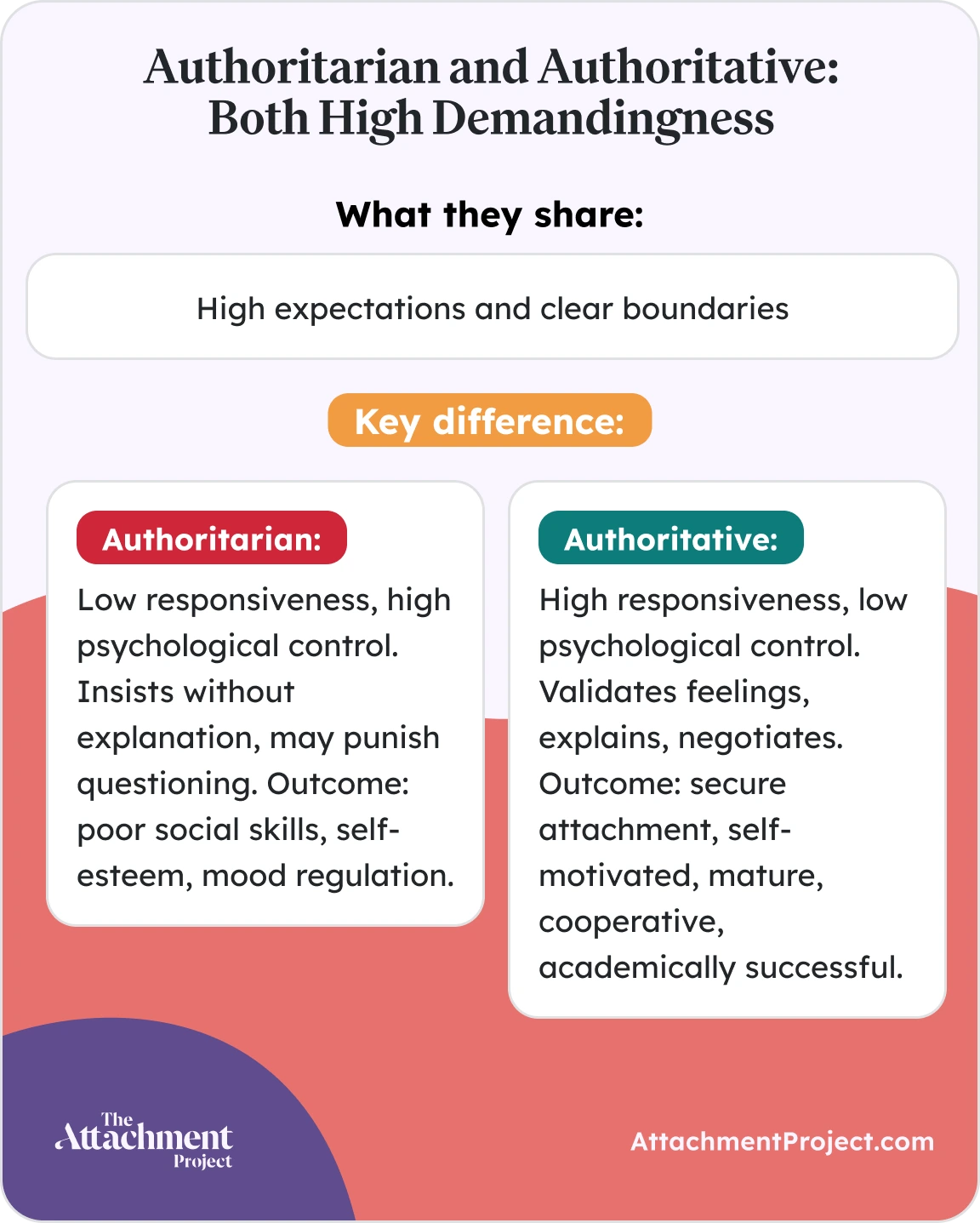

Parents with the authoritative style are assertive, but supportive – firm but fair. They are generally low in “psychological control”, meaning they give their children room to express themselves and question parental rules, even if it’s still expected that the rules are obeyed.

For example, your child asks to play with their friends instead of doing homework. As an authoritative parent, you might validate their desire to play with their friends but explain why homework is important and reinforce the expectation that they will do their homework first. Maybe you ask whether they’re stuck and offer to help, and maybe you negotiate with them so that they can play with their friends when their homework is done.

Outcomes of Authoritative Parenting

The authoritative parenting style has been associated with supporting secure attachment development, even up to 12th grade4. This is likely because authoritative parenting emphasises autonomy and support, two things needed for children to develop a sense of a “safe base” and ability to explore.

Children raised in authoritative environments tend to be more self-motivated and better at adjusting to new environments as preschoolers, and they continue to be more mature, independent, co-operative, and academically successful through childhood and adolescence5, 6.

This sets children up for greater success in relationships as adults – secure attachment styles are associated with greater self-esteem and emotional regulation, enabling us to navigate relationship challenges and make healthier decisions.

Authoritarian Parenting: The Strict Disciplinarian

The authoritarian parenting style is high in demandingness, but low in responsiveness. Even though it shares high demandingness with the authoritative style, the authoritarian style is uniquely high in psychological control.

In the homework example, an authoritarian parent would insist upon the child completing their homework without offering an explanation or curiosity. They might punish their child for even considering breaking the rules and may discourage them from spending time with those friends in the future, seeing them as a distraction or a bad influence.

Although this parenting style is often considered less ideal, researchers have suggested that it can be beneficial when raising children in high-risk environments. For example, low-income African-American parents may lean towards authoritarian parenting because learned obedience and respect for authority can keep their children safe; research has found that this does support their emotional and social development more than expected5.

Authoritarian Parenting and Insecure Attachment

Outcomes of authoritarian parenting vary depending on how strictly rules are enforced. For instance, if authoritarian parents use a high level of psychological control, children may be more likely to feel intruded upon and respond with frustration, defiance, and internalizing or externalizing problems3.

Although children with authoritarian parents develop the skills to succeed academically, they tend not to develop good social skills, self-esteem, and mood regulation7. Although they are given the structure to be autonomous, they are not able to explore and develop a safe base without emotional support. This can lead to developing an insecure attachment style, whether anxious or avoidant.

Studies have also found that intrusions and controlling behavior by parents can lead to attachment disorganization in infants8. A disorganized infant attachment style exists on top of one of the three organized styles (secure, avoidant, or anxious), and indicates a shut-down of the attachment system as the infant doesn’t know how to approach their caregiver. Attachment disorganization is likely to lead to an insecure attachment in adulthood.

TAKE OUR PARENTING STYLES ASSESSMENT

Permissive Parenting: The Indulgent Approach

Permissive parenting is high in responsiveness but low in demandingness. This means that the parent-child relationship is warm and supportive, but boundaries and expectations aren’t particularly clear.

In the homework example, the permissive parent would agree to let the child play with their friends instead of doing their homework. Although this makes everybody feel good in the short-term, it doesn’t support the child to develop a sense of responsibility and discipline.

Permissive Parenting and Attachment Patterns

The permissive parenting style has been associated with attachment anxiety in children, but also better social skills7, 9. This comes at the cost of their academic performance and behavior control, and studies vary in their reports of the effect on self-esteem5, 7.

Although the child has the support needed to develop a safe attachment base, they aren’t able to develop the autonomy to confidently explore. This is why both structure and support are needed to develop attachment security.

Uninvolved Parenting: When Parents Are Emotionally Absent

When a child has neither structure nor support, their parents fall into the “uninvolved” parenting style category. This style, added by Maccoby & Martin, is low in responsiveness and low in demandingness. This can be the result of the parent’s own mental health difficulties and other significant disruptions at home.

As above, in our homework example, the child would likely receive no direction when they ask their parent whether they can play with their friends. The parent does not validate their needs and encourage them to play, but they don’t encourage them to continue their homework either – they might seem entirely disinterested in the child’s request.

Moments of disinterest or disconnection are normal – this only crosses into a predictable parenting style when it becomes a consistent pattern of behavior.

Uninvolved Parenting Outcomes

The uninvolved parenting style leads to the most negative outcomes, giving children neither the emotional support to develop good social skills nor the structure to develop discipline7. Without a consistent model for relationships, it’s difficult for a child to form a secure attachment style. This can result in long-lasting impacts on their self-esteem, emotional regulation, and ability to maintain healthy relationships.

How Your Own Attachment Style Influences Your Parenting

Your parenting style could be influenced by your attachment style, even if you’re not aware of it yet.

The secure attachment style has been associated with the authoritative parenting style, in parents as well as their children10. If you have a secure attachment style, you may be more comfortable setting boundaries and expectations while simultaneously expressing love and care.

In one study, the permissive parenting style was associated with attachment avoidance, while the authoritarian parenting style was associated with attachment anxiety11. They also found that people with lower avoidance scores were more likely to have authoritative parenting styles. Other studies have found that authoritarian parenting can be associated with anxiety or avoidance11.

If you have an insecure attachment style, it can be more difficult for you to regulate your own emotions, set boundaries with others, and manage conflict in relationships. This can make striking the balance between warmth and structure a real challenge, resulting in intergenerational cycles: your grandparent’s parenting style impacted your parent’s attachment style, which impacted their parenting style, which impacted your attachment style, which impacts your parenting style – and so on.

The good news is that the first step to breaking these cycles is to become aware of them. Now that you know how parenting styles and attachment styles intersect, you can begin to understand how this shows up in your own family systems and consider how to break the cycle.

Cultural Context: Do Parenting Styles Work Differently Across Cultures?

It’s important to highlight that much of the research on parenting styles and attachment focuses on the white, middle-class demographic. This makes it difficult to apply the findings universally, and we should keep in mind that what works for one group doesn’t necessarily work for everyone – for instance, we discussed earlier that more authoritarian parenting styles are preferred when children are raised in less safe environments.

Some studies have found that cultures that are stereotyped for more authoritarian parenting actually lean towards authoritative parenting, which does seem to be beneficial for social development across ethnic groups in the USA3, 7. However, parenting styles have less of an impact on academic performance outside of the European American demographic, and demandingness appears to affect wellbeing for boys more than girls7.

Differences in outcomes across ethnicities could be related to differences in social meaning – if your parents and all your friends’ parents are strict, you might be less likely to feel othered or “hard done by” than you would if all your friends’ parents were permissive.

START YOUR ATTACHMENT HEALING JOURNEY

This is a crucial reminder that behavior as nuanced as parenting is difficult to put into boxes, even more so when you try to apply them to everybody. Even though the 4 parenting styles can be a helpful tool to better understand your parenting style, we should consider how our culture and environment plays into parenting behaviors and remain respectful of other cultural norms.

Can You Change Your Parenting Style?

Studies show that, yes, your parenting style can change over time12. This can happen even without our awareness, but with intention and effort, you can change your parenting style to suit your family’s needs.

To support your child’s attachment security, focus on giving them a healthy balance of emotional support and practical structure. Boundaries and clear, fairly enforced expectations help them to develop discipline, autonomy, and confidence in their skills, while emotional support helps them to develop social skills and self-esteem. This balance aligns with the authoritative parenting style.

Steps Toward Authoritative Parenting

First, if you want to shift your parenting approach, it can be helpful to get other caregivers on board. This not only provides social support for you, but also gives your child consistency.

It might help to write down your parenting goals and how you intend to achieve them – do you want to be more or less demanding, and how will you achieve this? How would you be more or less responsive? Refer back to these goals every few weeks to see how they’ve gone and assess whether you met them. If you didn’t, what got in the way? How could you manage that over the next couple of weeks?

Skills-based interventions have been shown to help parents to change their parenting styles in a matter of weeks13. Skills-based interventions can be provided by qualified mental health practitioners and are often in groups. They aim to teach practical tools for parenting with a focus on the here and now, unlike talking therapies which might focus on the past.

If you have an insecure attachment style, working towards attachment security can support your efforts towards authoritative parenting.

In summary, a few steps you can take towards authoritative parenting are:

- Get all caregivers on board.

- Write down your goals and evaluate your progress often.

- Look for skills-based interventions from mental health professionals.

- Work on a secure attachment style.

Conclusion

Parenting is a tough job, and every parent questions whether they’re doing the right thing at one time or another. Understanding your parenting style can help you to assess whether you’re parenting in a way that’s aligned with your goals and your child’s needs.

Baumrind’s model of 4 parenting styles provides a basic framework for understanding different approaches to parenting. In reality, parenting styles are extremely nuanced and subject to cultural differences and variations. The authoritative parenting style is generally associated with better outcomes and attachment security, but this isn’t always preferred across cultural contexts.

If you don’t feel that your parenting style is where you want it to be, don’t panic – you already have the awareness needed to change, and that’s a big step forward. With peer and professional support, you can change your parenting style and support your child to develop a more secure attachment style.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the best parenting style according to research?

Studies find that the authoritative parenting style (high responsiveness, high demandingness) is associated with the most positive outcomes for children.

Q: How do parenting styles affect attachment?

The authoritative parenting style is associated with secure attachment because it supports autonomy and confidence, while other parenting styles are associated with insecure attachment styles.

Q: Can I change my parenting style if I didn’t have good role models?

If you didn’t have good role models, you can still change your parenting style with awareness and intention.

Q: Is gentle parenting the same as permissive parenting?

Gentle parenting includes the use of set boundaries and expectations. Therefore, it is not the same as permissive parenting, which is high in warmth and empathy but low in rules and expectations.

Q: Is it too late to change my parenting style if my kids are teenagers?

It isn’t too late to change your parenting style if your kids are teenagers – parenting styles naturally evolve as your family changes, and parenting styles tend to change over time even without our awareness.

Q: Can authoritarian parenting work in some situations?

Authoritarian parenting is generally associated with poorer social outcomes, but studies tend to be focused on white middle-class demographics. Authoritarian parenting has been found to benefit children raised in more dangerous environments, such as low-income African-American children, as respect and obedience are associated with keeping children safe.

References

- Baumrind D: Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph 1971, 4:1-103

- Maccoby EE, Martin JA: Socialization in the context of the family: parent–child interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 4. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development. Edited by Hetherington EM. Wiley; 1983:1-102.

- Smetana JG. Current research on parenting styles, dimensions, and beliefs. Current opinion in psychology. 2017 Jun 1;15:19-25.

- Karavasilis L. Associations between parenting style and quality of attachment to mother in middle childhood and adolescence (Doctoral dissertation, Concordia University).

- McWayne CM, Owsianik M, Green LE, Fantuzzo JW. Parenting behaviors and preschool children’s social and emotional skills: A question of the consequential validity of traditional parenting constructs for low-income African Americans. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2008 Apr 1;23(2):173-92.

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological reports. 1995 Dec;77(3):819-30.

- Darling N. Parenting Style and Its Correlates. ERIC Digest. 1999 Mar.

- Gedaly LR, Leerkes EM. The role of sociodemographic risk and maternal behavior in the prediction of infant attachment disorganization. Attachment & Human Development. 2016 Nov 1;18(6):554-69.

- Eftekhari A, Bakhtiari M, Kianimoghadam AS. The relationship between the attachment styles of children, parenting styles, and the socio-economic status of parents. Journal of community health research. 2022.

- Doinita NE, Maria ND. Attachment and parenting styles. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015 Aug 26;203:199-204.

- Yahya F, Halim NA, Yusoff NF, Ghazali NM, Anuar A, Jayos S, Aren M, Othman MR, Mustaffa MS. Adult attachment and parenting styles. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering. 2019;8(1):193-9.

- Kaniušonytė G, Laursen B. Parenting styles revisited: A longitudinal person-oriented assessment of perceived parent behavior. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2021 Jan;38(1):210-31.

- Fujiwara T, Kato N, Sanders MR. Effectiveness of Group Positive Parenting Program (Triple P) in changing child behavior, parenting style, and parental adjustment: An intervention study in Japan. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2011 Dec;20(6):804-13.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox