Protest Behavior in Attachment: Why We Act Out When Feeling Insecure

You’ve waited all day for the person you’re interested in to text you back. You’ve felt ignored, anxious, and on-edge – so now that they’ve finally replied, you decide not to respond until tomorrow to make them feel the same way you did. You may not know it, but this is a form of protest behavior.

Protest behavior describes our indirect attempts to resolve an attachment disruption. Anxious attachment styles are particularly prone to using protest behaviors because their attachment systems are often overactivated, but anyone could engage in protest behavior under certain circumstances.

Today, we’ll talk about what protest behavior is, protest behavior and attachment, more examples of protest behavior, and how to stop protest behavior to cultivate healthier relationships.

Am I Being Manipulative? The Psychology of Protest Behavior

In psychology, the term “protest behavior” is usually used to describe how infants might react disruptively in response to separation from their attachment figures. When you see a young child cry when their parents drop them off at daycare, they are protesting to try to regain the connection with their caregiver.

This is normal for securely attached infants; one study found high levels of protest behavior in securely attached infants, but low protest behavior in insecurely attached infants – though it’s important to note that this group was almost entirely made up of infants with attachment avoidance and very few with attachment anxiety1.

Mary Ainsworth noted that anxiously attached infants showed protest behavior even when reunited with their caregivers, not just when separated, which lines up with our understanding of attachment anxiety as an upregulation of the attachment system2.

The reason securely attached infants use protest behavior is because it makes adults pay attention, effectively repairing the attachment bond – this is what the attachment system is designed to do.

Protest Behavior in Adulthood

In popular culture, “protest behavior” describes how adults might also protest when they feel their attachments are threatened. As adults, we have lots of ways of communicating our emotions other than screaming and crying, so adult protest behavior can take many different forms – even more so in the digital age.

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

However, protest behavior isn’t typically an effective way to communicate our feelings. Although it can temporarily repair an attachment disruption, it tends to cause more problems than it solves in the long run – so why do we continue to do it?

The Science Behind Attachment Protest Behaviors

During evolution, forming and maintaining attachments with other people helped to keep us safe. Our brains therefore developed mechanisms to promote attachments, which are initially formed in infancy and stay active throughout our lives.

Studies have found that brain areas associated with threat detection activate when our attachment systems are hyperactivated; amygdala activation increases in proportion with increases in attachment anxiety, which is also associated with brain areas that react to social rejection3.

Our brain’s stress response is also extra active when our attachment systems are activated, especially during conflict4. This starts with activation in the brain’s hypothalamus, which sets off a chain reaction throughout the body ending in the release of a stress hormone called cortisol.

All of this stress and anxiety that we can see in your brain during attachment activation can result in the urge to use protest behaviors to soothe these difficult emotions. However, protest behaviors are like putting a band-aid on a broken leg – dealing with the root of the problem is a longer, more difficult process, but it leads to more thorough healing.

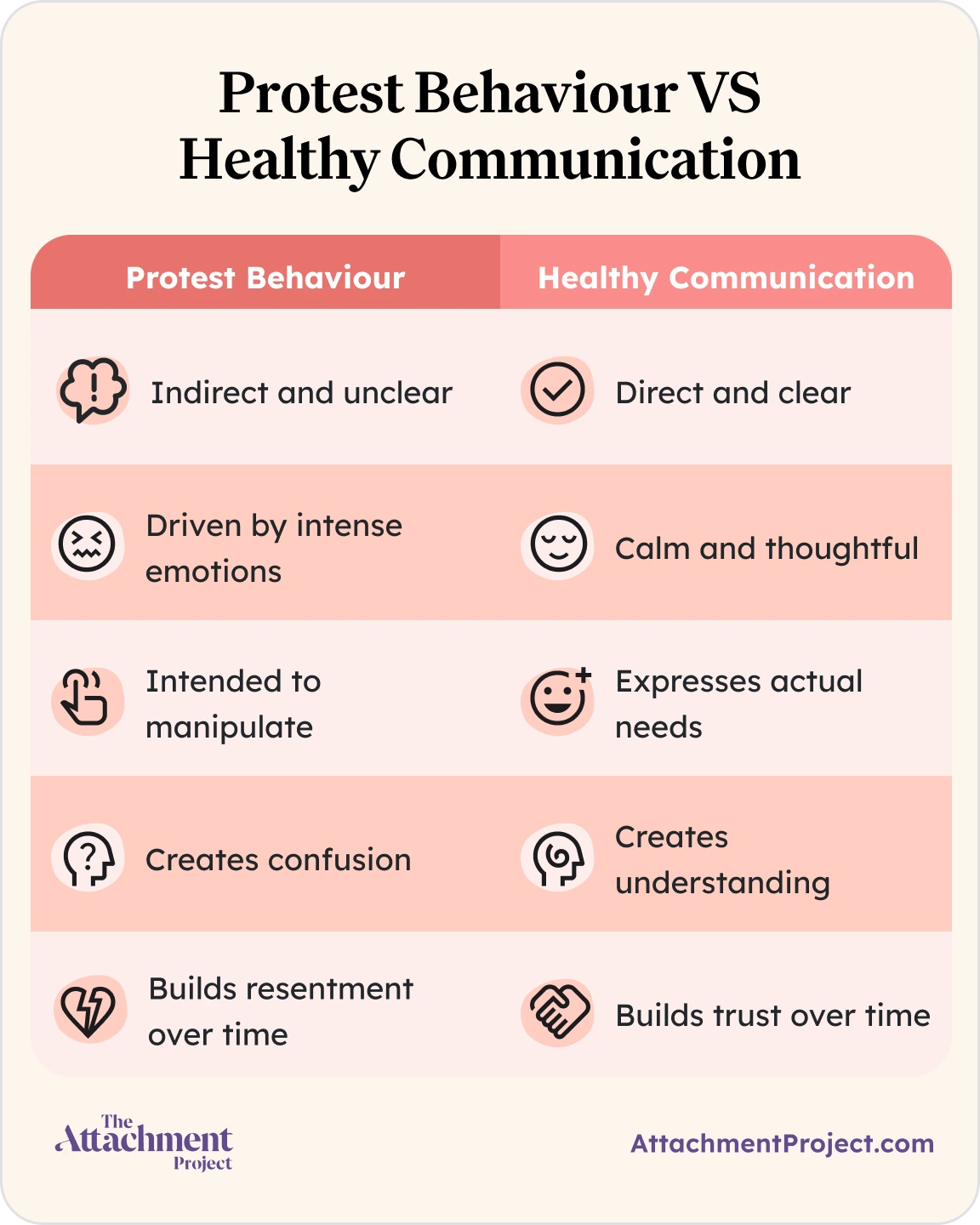

Protest Behavior vs. Healthy Communication

One of the most important distinctions between protest behavior and healthy communication is your intent. Are you acting because you want to resolve the problem, or because you want to resolve your discomfort? Do you feel you’re approaching it as a team, or are you trying to “get back” at your partner?

Expressing your needs clearly and openly can feel difficult, but it is a much easier way to solve problems in relationships. Your partner can’t read your mind, and protest behaviors are usually open to interpretation. For example, if you don’t text back for a long time on purpose because you want them to text you more, they’re more likely to think you’re just busy or sleeping than trying to prove a point.

When something like this happens, you might end up even more frustrated and having to explain to your partner that you ignored them on purpose. This can make your partner feel manipulated, confused, and upset, and they’re less likely to trust you in the future. Even if they do start to change their behavior, they might be doing this to avoid upsetting you instead of to show you appreciation or because they want to; this isn’t the foundation of a healthy relationship.

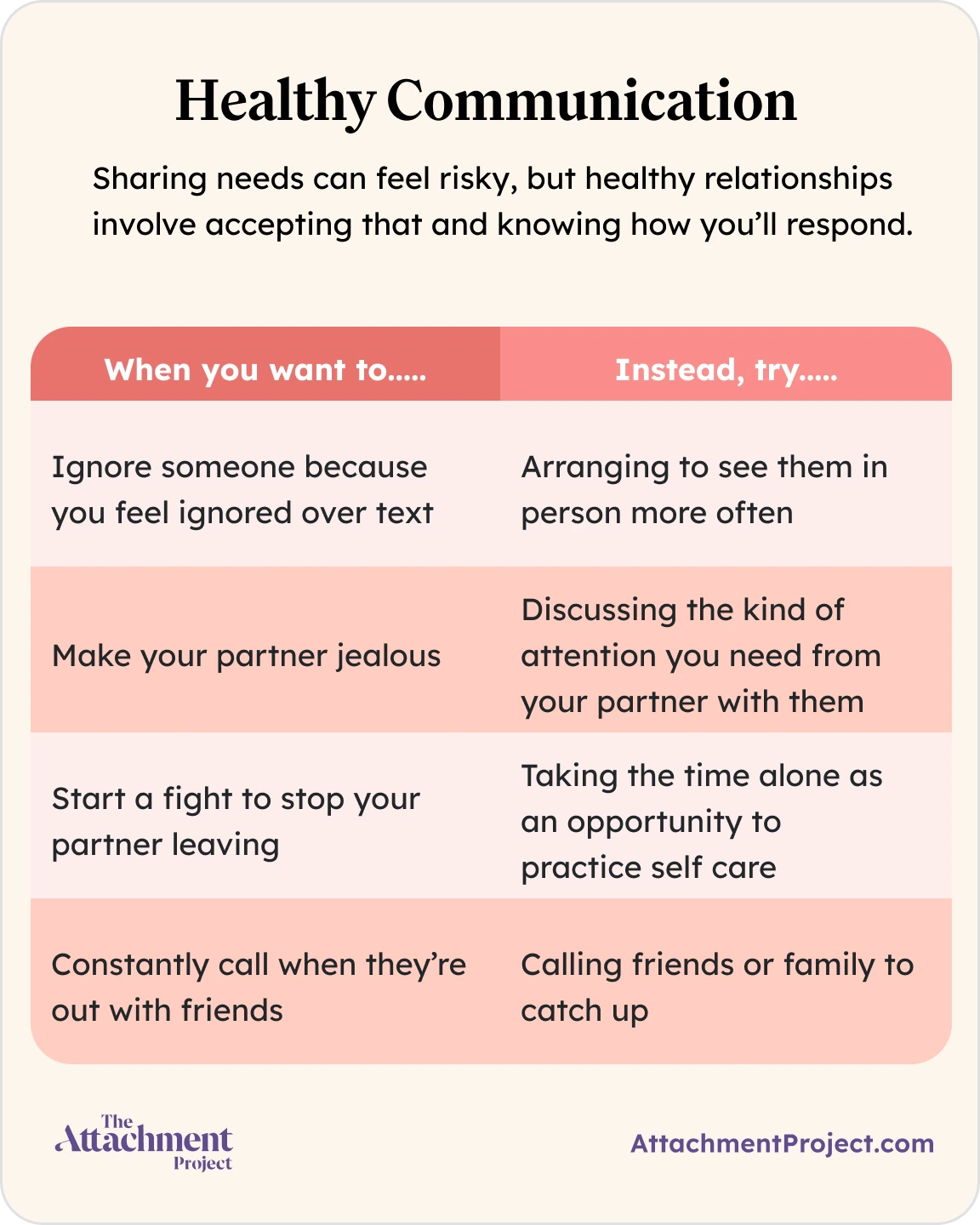

Examples of Healthy Communication and Alternative Behaviors

Communicating your needs directly is difficult because it does involve taking a risk. You might be worried that your partner won’t respond in the way that you want them to, or won’t be able to meet your needs – part of healthy relationships is accepting that this might happen, but knowing how you’ll respond if it does.

For example, if they aren’t able to meet your needs, would you still continue the relationship? Would you set new boundaries? Changing your relationship with someone this way can be tough, but it’s ultimately better for you, for them, and for your relationship than trying to change their behavior through manipulative tactics.

Do These Sound Familiar? Real Examples of Protest Behavior in Relationships

Any behavior that you might use to try to get your partner’s attention without properly communicating your needs could be considered protest behavior. In today’s digital age, protest behavior often comes in the form of ignoring or blocking someone online, posting things to get a reaction from a particular person, or deleting accounts to get attention.

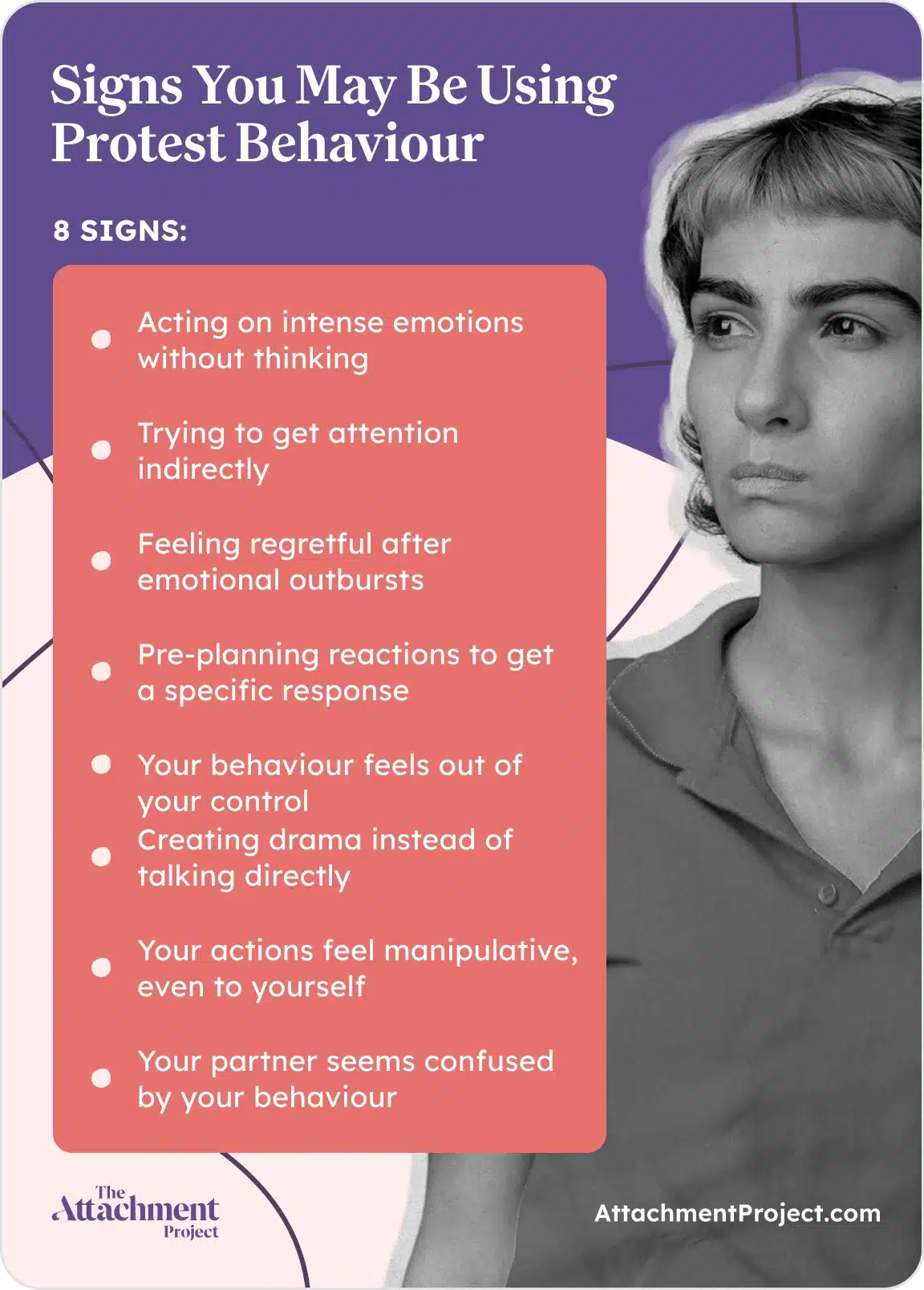

Most of the time, protest behaviors are unconscious processes – behaviors driven by strong emotional reactions, without proper forethought. If you’re engaging in unconscious protest behavior, you might have a sense that what you’re doing isn’t fully within your control, and you might feel regretful after acting on emotional urges.

If your protest behavior is conscious, then you might pre-plan what you’re going to do and what you hope the reaction will be. This is still driven by emotion, but it might not feel as impulsive.

START YOUR ATTACHMENT HEALING JOURNEY

Real Life Protest Behaviors

Even though social media changed the way we engage in protest behavior, we can still engage in the typical protest behaviors that happen face to face. These might include:

Emotional escalation and dramatic expressions of distress

Showing intense emotions is one way that we might try to get a response from somebody else. When we cry, scream, or yell, we often attract care and attention from others.

Clinging and excessive contact attempts

Physically clinging to a partner, especially during conflict, or making excessive attempts to be near them can be a form of protest behavior.

Silent treatment

Ignoring or stonewalling your partner can be a way of trying to get a response without directly communicating your feelings or needs.

Creating jealousy or threatening relationship security

Intentionally making your partner jealous by giving someone else attention can result in getting attention from your partner, even though it damages the relationship in the long term.

Physical support

If you want more care and attention from your partner, you might be more likely to ask them for help when you feel unwell or use physical symptoms to gain closeness.

Digital-Age Protest Behaviors

More examples of protest behaviors online include:

Withholding read receipts and delayed responses

Avoiding responding to somebody, leaving them on “read” – especially when they’re notified that you’ve read their message – or muting their messages to provoke a response from them is a form of protest behavior.

Social media posting to provoke partner attention

Posting things on social media with the intention of gaining attention from a specific person, whether in a negative or positive way, may also be protest behavior.

Online activity monitoring and checking behaviors

Do you regularly check your partner’s social media for updates? Do you check their phone or online accounts? This, too, could be a form of protest behavior, particularly if it’s intended to pick faults or feel a sense of control.

Digital breadcrumbing

Breadcrumbing is what it’s called when we give partners small pieces of hope with no intention of acting on them. Online, this might look like intentionally slow yet positive responses to messages, or talking about arranging to meet up in person without ever making a real plan. If you’re doing this to keep someone on the hook, you may be engaging in protest behavior.

Using dating apps while in relationships

Protest behavior can also include using dating apps while in a relationship to make your partner jealous or gain a reaction.

Attachment Styles and Protest Behavior Patterns

You might be wondering whether your attachment style influences how you engage with protest behavior – and you’d be right to think that it does.

When we have high attachment anxiety, we respond to conflict with heightened emotions and a desire to bring our partner closer. On the other hand, when we have high attachment avoidance, we tend to respond to conflict with flattened emotions and push our partner away. The fearful-avoidant attachment style is high in both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, resulting in more complicated dynamics.

If you have an insecure attachment style, high in anxiety, avoidance, or both, you might be more likely to engage in protest behavior or use it more intensely than people with a secure attachment style5.

Anxious Attachment and Hyperactivation Strategies

Anxious attachment behaviors come from an overactivated attachment system. This drives intense emotions, which can cause us to act on impulse. It also drives a strong fear of abandonment, which can make relationship conflict feel frightening and overwhelming. We might seek constant reassurance and validation from our partners, which can escalate quickly into protest behavior.

If you have an anxious attachment style, you might be more likely to use externalizing protest behaviors that draw partners closer such as clinging, emotional escalation, and posting online to provoke a reaction or gain attention.

How Dismissive Avoidants Engage in Protest Behaviors

While anxious attachment behaviors come from an overactivated attachment system, avoidant attachment behaviors come from an underactivated attachment system. When the relationship feels threatened, someone with attachment avoidance distances themselves to make the conflict less painful.

In avoidant attachment styles, protest behaviors are more likely to be the kind that create distance – avoiding messages, blocking, and the silent treatment, for example. One study found that, even though avoidant attachment styles denied feeling angry with their partner, they still showed physiological signs of anger and “smoldering hostility”6.

Fearful Avoidant Protest Behaviors

If you have a fearful-avoidant attachment style, you might experience both kinds of protest behavior, switching between an over- and underactivated attachment system. This comes from an internal conflict between wanting to keep your partner close when the relationship feels threatened and wanting to keep your distance to protect your emotions.

This push and pull dynamic can be confusing for you and your partner, and can cause relationship difficulties to escalate quickly – especially when protest behaviors are involved.

The Impact of Protest Behaviors on Relationships

Protest behaviors might work in the short term – ultimately, the goal of protest behavior is to feel better. But while the silent treatment might result in gaining your partner’s attention, or clinging and crying might make them stay home, these behaviors can cause resentment to build over time.

When our partners react the way we hope we will, it reinforces the behavior – it worked this time, so we’ll do the same thing to get the same reaction next time. While we feel better, our partners feel worse, and each time we use protest behaviors we erode trust and security in the relationship. This can cause our partners to distance themselves further, resulting in more frequent and stronger protest behaviors, leading to a worsening cycle.

People who have experienced the receiving end of protest behaviors describe it as a “painful” experience that ultimately ruins relationships. In the worst cases, protest behavior has been linked with partner abuse and escalation to violence5.

The Anxious-Avoidant Protest Cycle

This cycle of protesting and withdrawing can be particularly strong in relationships where one partner is high in anxiety (anxious-preoccupied or fearful-avoidant) and the other is high in avoidance (dismissive-avoidant or fearful-avoidant).

When the anxious partner engages in protest behavior to pull their partner closer, the avoidant partner feels trapped and pushes them further away, causing the anxious partner to try even harder to keep them close.

For example, when the relationship is going well – say, an important milestone has been reached, like an anniversary or meeting the parents – an avoidant partner might start to feel cautious and mistrusting of the relationship, and start to show signs of pulling away. The anxious partner, hypervigilant to relationship threats, might notice decreased communication and feel their fear of abandonment heighten.

In response to these heightened emotions, the anxious partner might engage in protest behavior like calling constantly while the avoidant partner is away. This can make the avoidant partner feel like they don’t have autonomy and freedom, causing them to turn their phone off and pull away even more. The anxious partner might respond by increasing their protest behavior even more, perhaps by crying and showing their intense distress when their avoidant partner comes home, and so the cycle continues.

Breaking the cycle requires both partners to understand their own and each other’s perspectives.

BUILD HEALTHIER RELATIONSHIP PATTERNS

How to Stop Protest Behavior

Knowing your own personal protest patterns is the first step to breaking the protest behavior cycle. It can help to understand your attachment style – if you don’t know your attachment style yet, our attachment quiz is a fast, simple, and free way to find out.

Once you have a better understanding of your own attachment style and attachment system triggers, you can begin to recognize them and change your behavioral reaction. Communicating your needs directly is difficult when emotions are high, so it’s important to learn to take a pause when we feel those tough emotions bubbling up and let them cool down before we respond.

It’s also difficult to remember our tools for emotional regulation when emotions are in control; practicing emotional regulation strategies is an ongoing process that we get better at over time, just like any other skill.

Self-Regulation Techniques for Managing Attachment Activation

One useful tool for emotional regulation is mindfulness. Mindfulness teaches us to be present and to notice our thoughts and feelings without judging ourselves (which often causes feelings of shame or guilt, intensifying those difficult emotions). This comes in useful when we need to take a moment to step back from conflict and pause before we act driven by emotion.

When we’ve been able to step back and notice our intense emotions, grounding tools can help us to bring our emotions back down. Grounding tools are useful in any situation where we feel disconnected from the present, e.g. anxious about the future, angry about the past, or dissociated. They remind us to focus on the present, whether by connecting us to the here and now through the senses (e.g. the 5-4-3-2-1 technique) or through our own self-talk (repeating the date, place you’re in, and any useful affirmations).

Direct Communication Strategies to Replace Protest Behaviors

When your emotions have come down, you’re ready to communicate directly. This can still be scary, and that’s normal and okay to feel, especially if you haven’t had experiences with these difficult conversations going well.

Go into these conversations prepared – know what you need, what you think will help, and where your boundaries are. For instance, if what you need is more attention, you might want to suggest a regularly scheduled date night. You might have boundaries around how your partner responds to this, e.g. if your partner responds with their own protest behavior, you intend to disengage and talk to them another time.

Remember that you’re a team – don’t blame your partner for how you feel, but explain why you feel that way and acknowledge their perspective too. Constructive communication is another skill that builds over time, like emotional regulation and grounding, and it’s okay if it’s difficult to navigate at first.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is protest behavior the same as being manipulative?

Protest behavior is intended to manipulate someone instead of expressing needs clearly, but it isn’t always a conscious decision – sometimes it’s driven by high emotions and feels out of control.

How can I tell if I’m protesting or just expressing my needs?

Protest behavior is used instead of direct communication of needs. If your communication is calm and clear, this is just expressing your needs. If your communication is unclear and driven by intense emotions, you may be using protest behavior.

What should I do when my partner exhibits protest behaviors?

If your partner is exhibiting protest behaviors, they may not be aware of it. It may be worth having a gentle discussion about the patterns you’ve noticed – approach this conversation with curiosity and openness, and avoid blaming and shaming them.

Can protest behaviors ever be healthy or necessary?

Protest behaviors are not a good example of healthy communication. If you feel that they’re necessary to communicate your emotions, it may be helpful to examine you and your partner’s communication patterns.

Is the silent treatment always a form of protest behavior?

The silent treatment isn’t always a form of protest behavior. Stonewalling is often mistaken for the silent treatment, but stonewalling isn’t intended to manipulate – rather, it’s an unintentional reaction to overwhelming emotions.

What’s the difference between protest behavior and emotional abuse?

Many forms of protest behavior are also considered emotional abuse, because these behaviors are typically intended to manipulate someone using their emotions.

References

- Ahnert L, Eckstein‐Madry T, Piskernik B, Porges SW, Lamb ME. Infants’ stress responses and protest behaviors at childcare entry and the role of care providers. Developmental Psychobiology. 2021 Sep;63(6):e22156.

- Stayton DJ, Ainsworth MD. Individual differences in infant responses to brief, everyday separations as related to other infant and maternal behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1973 Sep;9(2):226.

- Vrtička P, Vuilleumier P. Neuroscience of human social interactions and adult attachment style. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2012 Jul 17;6:212.

- Pietromonaco PR, Powers SI. Attachment and health-related physiological stress processes. Current opinion in psychology. 2015 Feb 1;1:34-9.

- Gottlieb L. Mating in close proximity: An investigation of the role of attachment styles on IPV perpetration in the time of COVID-19 (Doctoral dissertation, Brunel University London). 2023 Sept.

- Dutton DG. Attachment and violence: An anger born of fear. 2011 Jan.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox