How Fearful Avoidant Attachment Style Develops in Childhood

Published on June 7, 2021 Updated on April 6, 2023

Known as disorganized attachment style in adulthood, the fearful avoidant attachment style is thought to be the most difficult. Sadly, this attachment style is often seen in children that have experienced trauma or abuse.

The fearful avoidant attachment style occurs in about 7% of the population and typically develops in the first 18 months of life.

During this formative period, a child’s caregiver may have behaved chaotically or bizarrely. Sometimes the parent could even behave aggressively, causing the child to see them as “scary”.

This article will cover your top questions on fearful avoidant attachment in childhood including:

- When and how does fearful avoidant attachment attachment develop in childhood?

- What are common behaviors of caregivers with fearful avoidant children?

- How does the child with fearful avoidant attachment perceive the caregiver’s behavior?

- Is your child fearful avoidant? Were you a fearful avoidant child? Check these common behaviors and characteristics of fearful avoidant children.

- How does fearful avoidant attachment affect the child?

- How can a child be raised to have secure attachment?

- What are the five conditions required to raise a child with secure attachment?

How do attachment styles form in childhood?

A child’s attachment style is formed through the type of bond that builds between themselves and their caregivers. Through the way that their parents met their needs, a child forms expectations about their world and the people in it.

This outlook has a big impact on many other areas of the child’s life. For instance, from how willing they are to explore their environment, to how they socialize with other children and adults. It even affects how they will behave in adult relationships.

The following table contains the different attachment style names, including how they change from childhood to adulthood:

| Attachment Style | In Childhood | In Adulthood |

| Secure | Secure | Secure |

| Insecure | Anxious-ambivalent | Anxious-preoccupied |

| Insecure | Anxious-avoidant | Avoidant-dismissive |

| Insecure | Fearful Avoidant | Disorganized |

How does fearful avoidant attachment develop?

Fearful avoidant attachment develops in children when caregivers often exhibit contrasting and unpredictable behavior

The caregivers might show contrasting behavior towards how they parent their child. For example, they might be highly loving at times, but on other occasions, they might not even meet the child’s basic needs. As a result, this creates a sense of fear within a child for their own safety.

The fearful avoidant child subconsciously realizes that their caregiver cannot meet their needs.

The caregiver’s behavior isn’t always intentional

The caregivers of fearful avoidant children may not intentionally behave this way. Oftentimes, caregivers parent in the way that they themselves were parented. As a result, they may lack confidence in their own ability to successfully raise a child. They might be overwhelmed and scared, thus, the child is frightening to them.

This can cause the caregiver to behave unpredictably. For example, on one instance they might laugh and reward a specific behavior of their child, but another time, they might become outraged and punish them for the exact same behavior.

The child’s caregiver – the person that they desire closeness with above all others – is a source of alarm.

Due to these unpredictable and chaotic actions, fearful avoidant children often struggle to understand how to get their needs met as they can’t adapt to their parent’s behavior. It’s just too unpredictable.

Thus they end up confused and conflicted about how they should act; their experience is that of fear without a solution.

Let’s quickly recap how a fearful avoidant child’s caregivers might act:

- May behave erratically or bizarrely, causing their child to see them as “frightening”

- Might exhibit contrasting and unpredictable behaviors towards their child, such as acting affectionate on one hand and aggressive on the other without a clear rationale

- They potentially had a chaotic childhood of their own

- Might be overwhelmed by the prospect of parenting as they lack confidence in their abilities

How does a fearful avoidant child behave?

After the Strange Situation experiment in 1969, Mary Ainsworth‘s colleague Mary Main noted that when a baby’s mother left the room, the securely attached children became very upset. Once she returned, these children instantly ran to her for comfort and affection. After that soothing moment, they happily resumed playing by themselves.

However, in contrast, a child with a fearful avoidant attachment will act conflicted towards their caregiver. They may at first run to them, but then seem to change their mind and either run away or act out against their mother.

As is symptomatic of their attachment style, they desire comfort and closeness with their caregiver, but as soon as they got near them their fear of them was triggered.

A baby or a young child with a fearful avoidant attachment might behave in bizarre ways.

- For example, they might stare at their parent but avoid eye contact.

- They may scream endlessly as if in an attempt to engage their caregiver.

- Lastly, they sometimes show conflicting actions such as seeking attention and then shutting it down promptly.

Fearful avoidant children do not feel safe and secure in the world

A slightly older child with a fearful avoidant attachment might find it hard to self-soothe. Further, they may struggle with opening up to other people. Since they do not feel safe and secure in the world, so they’re always looking out for the next negative event.

Fearful avoidant children sometimes have no sense of personal boundaries. For example, they might discuss intimate and inappropriate details with people unfamiliar to them. They may also only be able to maintain short and superficial interactions with others.

What’s more, they tend to show no bias between people familiar to them and strangers. They may lack a sense of guilt, show flighty behavior and difficulty in concentrating. They also often have a hard time keeping long-term friends or deep relationships.

Sometimes, children with a fearful-avoidant attachment style require professional help. Otherwise they could be at risk of carrying these behaviors into adulthood and their relationships.

To recap, a child with a fearful avoidant attachment style may:

- Behave conflicted towards their caregiver

- Desire comfort and love from their parent, but also fear them

- Exhibit seemingly unexplainable behaviors, such as staring without eye contact

- Have difficulties with self-soothing

- Have difficulties allowing themselves to be vulnerable around others

- Lack personal boundaries

- Not feeling secure in their world

- Struggle to maintain meaningful interactions

- Not discriminate between people unfamiliar to them and strangers

How can a fearful avoidant child be raised to develop a secure attachment?

There is no parenting handbook, so, at times, it can be a tricky area to handle. How much attention and love are too little, and how much is smothering?

Fortunately, children are born with strong survival instincts based on their inability to survive on their own and their reliance on adults for love and safety. Thus, they give out signals to notify their caregivers that they need something.

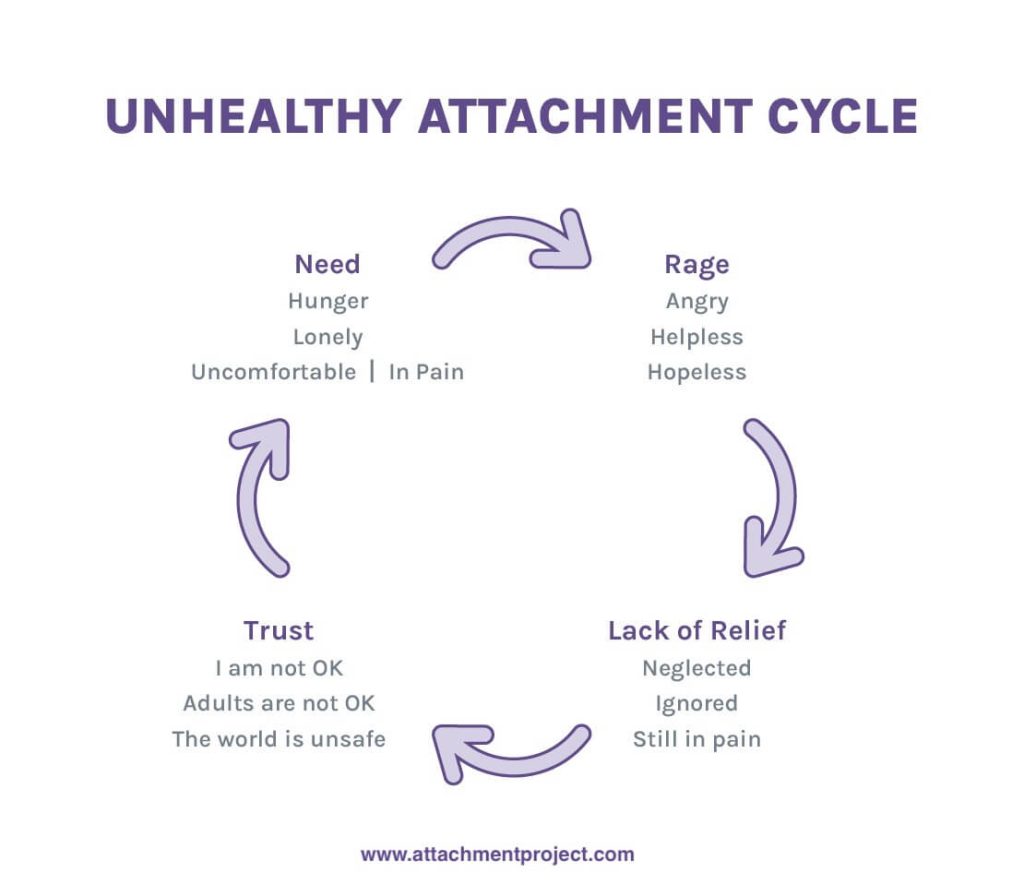

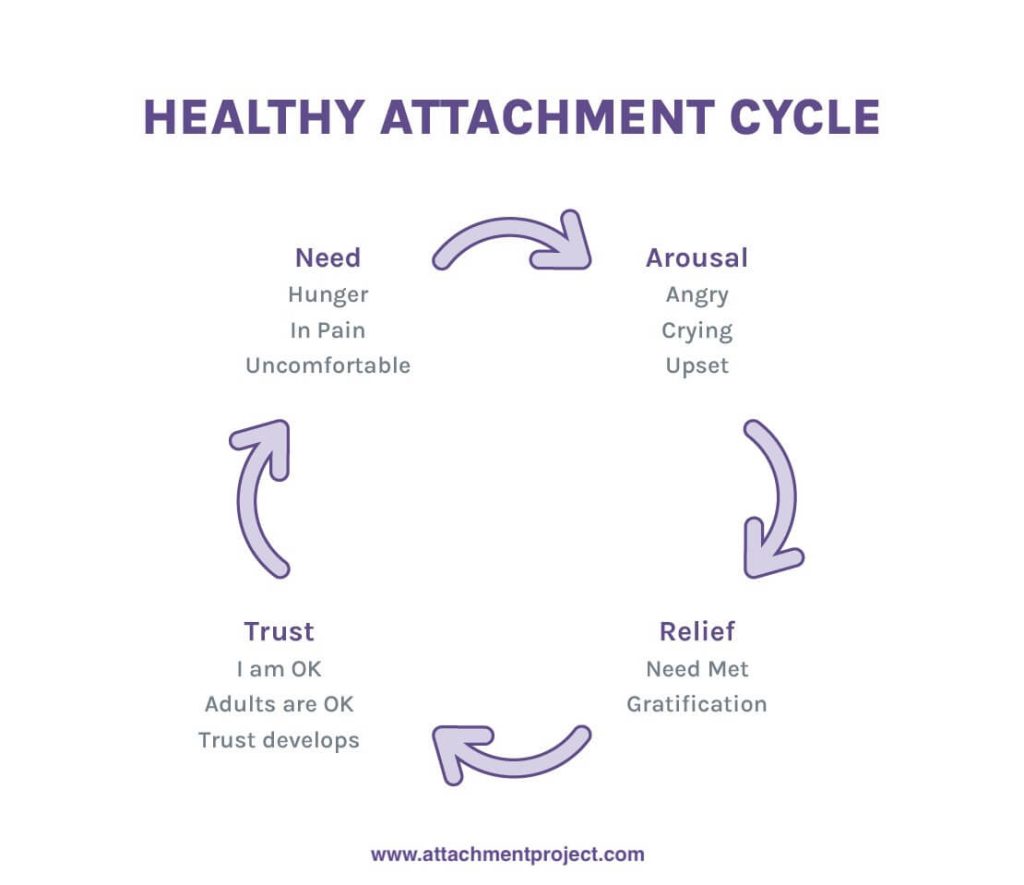

How the parent responds to these cues from their children can be different between a secure and insecure attachment style. The chart below shows what happens in a healthy cycle.

The Five Conditions for raising a securely attached child

In order to raise a securely attached child, there are five key areas that a caregiver should strive to fulfill (Brown & Elliott, 2016):

1. The child feels safe

First, a child needs to feel secure and safe in their world in order to thrive.

For a baby or toddler, their caregiver is their prime source of safety. For example, if they are around, the child will feel confident that no harm will come to them, that they will be fed, and kept warm.

Yet it’s important to cater to the child’s needs with a certain amount of awareness. Caregivers should allow children the chance to develop independence while still letting them know that they are nearby.

The caregiver is the child’s barrier against harm, letting them know that they are protected and loved.

2. The child feels seen and known

Secondly, we have what we refer to in the attachment field as “attunement”.

For a young child, their cues (cries and signals) are their outward voice to let their caregiver know what they want and need. It is, therefore, vital that the caregiver correctly reads these cues.

If the parent is in tune with the child’s cues they will respond in the proper way. Thereby letting the child know that when they need something, they can signal for it and it will be given.

This gives the child a sense of freedom; their world is reliable, and above all they can exert a certain amount of control over it.

3. The child is comforted

Certainly, to raise a securely attached child, caregivers need to be open, warm, and inviting.

After all, the world can sometimes be a scary place to a small child. For instance, if the child experiences any disappointments, they need to know that their caregivers will be there to help soothe them.

In time, the child learns to recognize this as the norm and as they grow up, they use their caregiver’s actions as the template for managing their own upsets.

4. The child feels valued

In addition, we have the process of building a healthy self-esteem. Value for who we are as a person starts as a baby.

As a result, caregivers should aim to express joy and pride over who their child is rather than over what the child does.

The child starts to realize that they are valuable – unconditionally – from what they achieve.

5. The child feels support for being their best self

Finally, a child should feel supported to happily explore their world. To achieve this, a parent needs to believe in their child’s ability. In case anything goes wrong, the parent should stay close to the child.

By doing so, they’re allowing the child to grow while watching from a safe distance. In turn, the child will develop a sense of freedom to explore and develop a strong sense of self.

Further reading related to fearful avoidant attachment

This article is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to knowing how to raise a child with a secure attachment.

If you’re interested in knowing more, then we suggest reading secure attachment from childhood to adult relationships and disorganized attachment in adult relationships. We also recommend the book The Importance of Love Rays by attachment specialist Paula Sacks.

If you prefer to go the route of a workbook, we recently released our first series of attachment style digital workbooks.

Our new disorganized attachment digital workbook includes:

- 193 pages with 36 practical exercises

- How disorganized attachment affects you in over 10 different areas of life

- Groundbreaking and up-to-date research on disorganized attachment

- An easy-to-digest intro to attachment theory

- Case studies, summaries, and reflection sections

Sources:

Bowlby, J. (2012). A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory. London: Routledge.

Brown, D. P., Elliott, D. S. (2016). Attachment Disturbances in Adults: Treatment for Comprehensive Repair. New York: W.W. Norton.

Salter, M.D., Ainsworth, M.C., Blehar, E.W., Wall, S.N. (2015). Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox