BPD and Attachment Styles

If you or your partner have borderline personality disorder (BPD), the impact it has on your relationship is likely a familiar story. Somebody with BPD experiences intense emotions, which they find difficult to control, and fear of abandonment – all leading to repeated relationship disruptions. If you’re the partner of somebody with BPD, your instinct may be to reassure and validate your partner, but this can sometimes lead to a spiralling of emotions and worsening of the existing attachment dynamic.

Although it takes time and intention, people with BPD can build secure attachment styles and healthier relationships. In this article, we’ll cover the main impact of BPD on relationships, the connection between BPD and attachment styles, the “favorite person” phenomenon, how people with BPD can develop more secure attachments, and how partners of people with BPD can support their loved one and themselves.

Key takeaways:

- BPD is characterized by intense emotions and tumultuous relationships.

- Attachments in BPD can be very insecure and difficult to navigate.

- Particular therapies can help people with BPD to learn emotional regulation and communication skills.

- People with BPD can practice skills at home to help them cope with emotions.

- It’s important to support yourself and collaborate on boundaries while supporting a partner with BPD.

What is Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)?

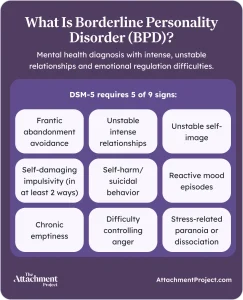

Borderline personality disorder is a mental health diagnosis characterised by intense, unstable, and unpredictable relationships, as well as difficulties with impulsivity and emotional regulation.

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

According to the DSM-5, used by clinicians to aid diagnosis, BPD is a pattern of difficult relationships, poor self-image, unstable mood, and impulsivity, indicated by at least 5 of these 9 signs1:

-

- Frantic avoidance of abandonment, whether real or imagined.

- A pattern of unstable and intense relationships that alternate between idealizing and devaluing the other person.

- Unstable self-image and identity.

- Impulsivity in at least 2 behaviors that can be self-damaging, such as impulsive spending, reckless driving, or binge eating.

- Self-harming and suicidal behavior.

- Episodes of highly reactive mood that last from hours to a few days, marked by high anxiety, irritability, or anger.

- Chronic feelings of emptiness.

- High anger and difficulty controlling it.

- Stress-related paranoia or severe dissociative symptoms.

Studies have found that up to 2.7% of American adults have BPD – to put that into perspective, that’s almost double the percentage of Americans with peanut allergies2, 3.

Since BPD is so common, researchers have spent a lot of time trying to understand how BPD forms in childhood. There are a few different theories, but the consensus is that BPD develops from a combination of adverse childhood experiences and a biological predisposition to emotional instability. This implicates the attachment system in the development of BPD, so the connection between BPD and attachment theory has been well studied.

Why Are Attachment and BPD So Closely Connected?

Attachment theory states that your mental map of the world, called your internal working model, forms based on the attention you receive from your caregiver as a child. If your caregiver is reliable, you understand that the world is safe and trustworthy and develop a secure attachment style. If your caregiver is inconsistent, you learn that attention is fickle and develop an anxious attachment style. If your caregiver is predictably unavailable, you learn that others will not come to help you and develop an avoidant attachment style.

Your attachment style can change over time depending on later life experiences. In adulthood, we measure attachment styles based on the domains of anxiety and avoidance. This results in a fourth attachment style: fearful-avoidance, where both anxiety and avoidance are high.

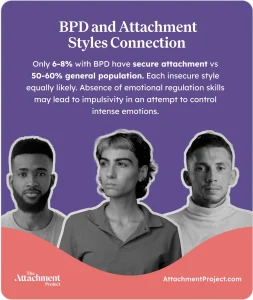

Insecure attachment styles have been associated with BPD – in one study, only 6-8% of a sample of people with BPD had secure attachment styles, compared with around 50-60% in the general population4. However, there was no specific pattern found in the 92-94% of the BPD population with insecure attachment styles; this means that each insecure attachment style was equally likely.

It’s possible that, while the same negative attachment experiences can be associated with BPD, each person has a different way of dealing with them resulting in either high anxiety, avoidance, or both. In both attachment anxiety and avoidance, there is an absence of emotional regulation skills that people with secure attachments typically learn in childhood. In BPD and insecure attachment, impulsive behavior could be part of attempts to control intense emotions5.

Disorganized Attachment and BPD Development

Some children don’t always fit one of the three infant attachment styles; if they have experienced severe attachment disruptions, such as feeling fear at home or severe separation, their attachment system may shut down in the presence of the caregiver. These infants are classified as having a disorganized attachment style on top of their usual attachment style, which typically leads to any one of the 3 insecure attachment styles in adulthood6, 7. Some disorganized attachment behaviors are similar to the fearful-avoidant attachment style, so you might see the two used interchangeably (even though they’re slightly different).

Disorganized attachment is also associated with BPD, with one study finding that unresolved attachments (also used interchangeably with disorganized) are higher in the BPD population8. The same attachment disruptions that lead to attachment disorganization could be part of the development of BPD – if you are genetically predisposed to BPD and experience severe attachment disruption in childhood, you may be more likely to develop both BPD and a disorganized attachment style5, 9.

The experiences that lead to attachment disorganization may be traumatic, but trauma is not necessary for either BPD or disorganized attachment styles to develop. Any stressful event or adverse experience early in life could contribute to BPD or attachment disorganization, including experiencing a caregiver who shows disorganized attachment behavior themselves as this can be confusing or frightening to an infant9, 10.

What Does Love Look Like When You Have BPD?

Borderline personality disorder can make relationships very challenging – the intense fear of abandonment, difficulty with emotional regulation, and impulsive tendencies can get in the way of healthy, stable connections. Even if you did have a secure attachment style as a child, the negative experiences with others that these symptoms can lead to can develop an insecure attachment style in adulthood.

If you have BPD, attachment anxiety and avoidance can both be especially intense experiences. You might feel terrified that your partner will leave, so you act impulsively on your emotions to get them to stay, which sometimes leads to us doing things we wouldn’t normally do or saying things we don’t mean. On the other hand, you might push them far away to protect them or yourself from these actions, resulting in avoidant behaviors such as ignoring them or downplaying your connection. You might find yourself cycling between the two in a fearful-avoidant pattern.

What is a “Favorite Person” and Why Does This Happen in BPD?

Some people with BPD talk about a unique attachment phenomenon called their “favorite person”. This isn’t currently a clinically recognized part of BPD, but psychologists have begun to look into it. One study coded social media posts on BPD forums about the favorite person or “FP” phenomenon, and arrived at the following definition11:

“FP may be defined as an insecure attachment figure who consumes the thoughts and evokes the abandonment fears of individuals with BPD. The FP is viewed as a rescuer and depended on for a sense of identity and emotional validation. Reactivity of mood and a tendency to hypermentalize around the FP may contribute to the instability evident in these relationships.”

In short, the favorite person represents validation and emotional support, and the person with BPD can overthink and make assumptions about the FP’s thoughts and feelings from their place of fear. The FPs can be romantic partners, friends, or family members, but whatever the relation is, they’re usually someone who is very accepting and validating of the person with BPD12.

Unfortunately, the reassurance and validation that FPs offer tends to make BPD symptoms worse12. FPs spending time with other friends or not being available when needed can induce jealousy, anxiety, and paranoia, and when they return to reassure the person with BPD that they’re not abandoning them, they can inadvertently reinforce insecure attachment patterns.

Because of this cycle, the relationship between the person with BPD and their favorite person tends to get worse over time. People with BPD can “split” on their favorite person, shifting from putting them on a pedestal to devaluing them based on the FP’s ability to meet their needs. This is what’s known as the idealization and devaluation cycle.

Idealization and Devaluation Cycles

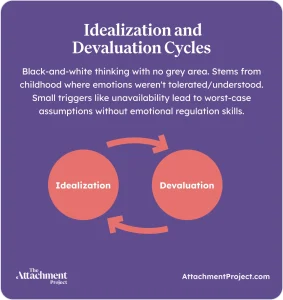

The idealisation and devaluation cycle is a form of black-and-white thinking – a cognitive distortion where things are either one way or another, good or bad, with no room for grey area or nuance.

According to American psychologist Marsha Linehan, whose work has been transformative in the field of BPD, these extremes in thinking arise from a childhood where emotional expression is neither tolerated nor understood. The child then doesn’t learn to tolerate or understand their own emotions13.

This means that the trigger for splitting could be smaller than you think – any perceived abandonment, such as unavailability, could lead someone with BPD to see the worst possible outcome. Without the ability to trust in others and feel self-assured without their presence, it can be very difficult to form secure attachments.

BPD Triggers and Emotional Dysregulation in Attachment

Any absence, rejection, or criticism could trigger attachment insecurity and unregulated emotions in BPD. When emotions are unregulated, it can be very difficult to identify what they are – let alone counteract or rationalize them. People with emotional dysregulation report intense and painful emotions in response to everyday rejection – although the trigger may be minor, they feel it as though it were a major event.

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

People with BPD understand that their emotional responses can be disproportionate, but, with or without BPD, our brains cannot reason while in highly emotional states. BPD can involve high rejection sensitivity, and people with BPD may feel physical pain while their emotions are activated; many describe feeling as though their nerves are constantly exposed. In one neuroimaging study, people with BPD had higher activation in brain areas associated with physical pain and emotional distress when viewing attachment content8.

Some people with BPD experience a feeling of dissociation or separation from their body, which can happen when our emotions are so overwhelming that they exceed our capacity to feel them.

With all this working against them, it’s understandable that people with BPD can find it difficult to maintain healthy relationships and build secure attachment styles – is it possible to develop attachment security with BPD?

Can People with BPD Develop Secure Attachment?

In short – yes, you can have healthy relationships and form secure attachments with BPD. One of the most popular therapies for BPD is Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), developed by Linehan, which teaches emotional regulation skills and problem solving14. After one year of DBT, neuroimaging studies show that the brain’s response to attachment is the same for people with BPD and the rest of the population – the pain and distress activation disappears15.

When we relearn our attachment styles, we literally reorganize our brains16. This process is called neuroplasticity – during childhood and adolescence, when we’re learning and growing the most, our brains have the greatest capacity for neuroplasticity, but we retain an ability to change and restructure our neurons throughout our lives. This means that it’s possible, through time and positive experiences, to gain an “earned” secure attachment. If someone with BPD is able to manage their symptoms and experience positive relationships with others, there’s no reason they can’t develop a secure attachment style.

Developing a secure attachment style involves the intention to change, positive attachment figures, redefining how you derive self-worth from others, and making peace with past experiences17. In BPD, it can be particularly helpful to work with a therapist.

What Types of Therapy Actually Help with BPD Attachment Problems?

As we discussed earlier, DBT is well suited to BPD – it combines group skills-based sessions with one on one therapy over a set period of time, which can vary between providers. The emotional regulation skills taught in DBT can help people with BPD to maintain healthier relationships, building more secure attachments over time.

Another popular option for BPD is mentalization-based therapy, or MBT. MBT is grounded in attachment theory and aims to improve your ability to understand other people’s behaviour – or, your ability to mentalize. This has been proven effective in BPD, particularly in reducing relationship difficulties as the person with BPD learns to see the other person’s behavior from more grounded and less extreme perspectives18.

If attachment is the main concern, attachment-based therapy can help you to understand how an insecure attachment might have formed and rebuild it with trust and safety.

How to Create Better Relationships When You Have BPD

When you have BPD, practicing emotional regulation and communication skills is often the key to healthier relationships. We know that it’s easier said than done, and even with professional support it can take months to years to build a secure attachment style – but each small step in the right direction brings you closer to your goal.

Mindfulness is an important part of DBT, and it’s something we can all practice. Mindfulness is often confused with relaxation, but it’s actually an important skill that enables you to observe your own thoughts and feelings and build emotional awareness. You can practice mindfulness using self-guided meditations, or try more creative activities like journaling or art.

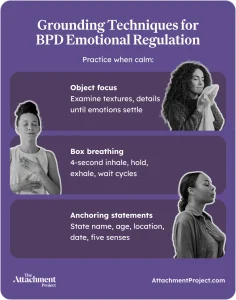

Self-soothing and grounding techniques can also help when emotions run high. It might seem counterintuitive, but it’s important to practice these techniques when you’re already feeling calm and present – this helps you to build the skill like a muscle, so that it comes naturally when you need it.

A few grounding techniques you can practice include:

-

- Object focus: Pay extremely close attention to a neutral object near you, like a cup or a book: concentrate on the textures and feel of it. How and where do you think it was made? How much do you think it will weigh if you pick it up? How much does it actually weigh? Consider every aspect of the object until the emotion has started to come down.

-

- Box breathing: Practice a breathing technique, such as box breathing: inhale for 4 seconds, hold for 4, exhale for 4, hold for 4, and repeat. Again, pay close attention to every breath. Where do you feel it? Is the air warm, or cold? Different people prefer different breathing exercises – you can try different counts or techniques until you find one that works best for you.

-

- Anchoring statements: In your mind or out loud, repeat your name, age, where you are, what the date and time is, and what you can see, hear, smell, taste, and touch. This anchors your mind in the present. Do this as many times as you need to.

It may be difficult to see how grounding techniques can be helpful, especially while you practice them from a place of calm, but being able to stay present and focus on something other than high emotions can help you to get through intense reactions without acting on impulse.

How to Help Someone with BPD Without Losing Yourself

If you have a partner with BPD, it’s important to understand as much as you can about how they experience relationships. Try to communicate openly with them about their thoughts and feelings, and agree on boundaries together in a way that feels collaborative rather than restrictive. It might help to discuss how extra reassurance and validation can intensify BPD symptoms and decide how you can make your partner feel supported without encouraging this dynamic.

Sometimes, even after good communication and boundary setting, your partner might still find it difficult to rationalize when their attachment patterns are activated. If their actions are taking a toll on your mental health, it’s important to look after yourself too – putting yourself first is not a lack of empathy or love, but a necessary step in being able to support your partner going forward. Be sure to nurture your relationships with your friends and family and communicate your needs to your partner, and take time for yourself so that you can continue to be there for your partner in a healthy capacity long-term.

From Chaos to Security: Healing BPD Attachment

Healing insecure attachment when you have BPD can be a long and difficult journey, but it is possible. Finding the right therapy and support for you can be gamechanging, although it may take time to find a therapist that works for you. It’s okay to try different therapists until you find one you resonate with.

The road to recovery won’t be linear – there will be plenty of setbacks along the way, and sometimes it might feel like you’re back at square one, but this is all a normal part of the process. Use your setbacks to learn what went wrong and what you could do differently next time, and don’t forget to celebrate your wins, however small they may seem. Remember to treat yourself with patience, kindness, and compassion; you are worthy of these things, and you’re doing your best with the experiences you have been given.

FAQs About BPD and Attachment

What attachment style do people with BPD typically have?

People with BPD typically have one of the 3 insecure attachment styles. In one study, only 6-8% of people with BPD had secure attachment styles.

Can someone with BPD have a healthy relationship with their favorite person?

It’s possible for someone with BPD to have a healthy relationship with their favorite person, although the term implies an already unhealthy relationship dynamic. It’s important to be empathic and understanding of your favorite person’s needs.

Why do people with BPD become obsessed with certain people?

When someone is very understanding and validating of someone with BPD, the person with BPD may start to rely on them heavily for emotional support and intensely fear abandonment.

Can BPD attachment patterns change without therapy?

You can take steps toward a secure BPD attachment pattern without therapy, but some therapies have been shown to be very effective in reducing BPD symptoms.

How can I support a partner with BPD attachment issues?

Excessive validation can lead to a downward spiral in BPD – try to set boundaries collaboratively and support your partner without falling into an intense push-pull dynamic.

Is the favorite person relationship always unhealthy?

By definition, the favorite person relationship is an unhealthy dynamic. However, this dynamic can change with healthy boundaries and mutual understanding.

What role does emotional dysregulation play in BPD attachments?

Emotional dysregulation makes it difficult to control reactions to relationship disruption. In BPD attachments, this could lead to high anxiety or avoidance, or both, as the person with BPD doesn’t know how else to cope with their intense feelings and fear of abandonment.

References

-

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edn). APA, 2013.

- Chapman AL. Borderline personality disorder and emotion dysregulation. Development and Psychopathology. 2019 Aug;31(3):1143-56.

- Lange L, Klimek L, Beyer K, Blümchen K, Novak N, Hamelmann E, Bauer A, Merk H, Rabe U, Jung K, Schlenter W. White paper on peanut allergy–part 1: Epidemiology, burden of disease, health economic aspects. Allergo journal international. 2021 Dec;30(8):261-9.

- Levy KN. The implications of attachment theory and research for understanding borderline personality disorder. Development and psychopathology. 2005 Dec;17(4):959-86.

- Mosquera D, Gonzalez A, Leeds AM. Early experience, structural dissociation, and emotional dysregulation in borderline personality disorder: the role of insecure and disorganized attachment. Borderline personality disorder and emotion dysregulation. 2014 Oct 28;1(1):15.

- Taunton M, McGrath L, Broberg C, Levy S, Kovacs AH, Khan A. Adverse childhood experience, attachment style, and quality of life in adult congenital heart disease. International Journal of Cardiology Congenital Heart Disease. 2021 Oct 1;5:100217.

- van Bussel EM, Wierdsma AI, van Aken BC, Willems IE, Mulder CL. The Associations between Attachment, Adverse Childhood Experiences and Re-Victimization in Patients with a Psychosis Spectrum Disorder. Medical Research Archives. 2024 Jul 31;12(7).

- Bernheim D, Buchheim A, Domin M, Mentel R, Lotze M. Neural correlates of attachment representation in patients with borderline personality disorder using a personalized functional magnet resonance imaging task. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2022 Feb 24;16:810417.

- Steele H, Siever L. An attachment perspective on borderline personality disorder: Advances in gene–environment considerations. Current psychiatry reports. 2010 Feb;12(1):61-7.

- Cattane N, Rossi R, Lanfredi M, Cattaneo A. Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: exploring the affected biological systems and mechanisms. BMC psychiatry. 2017 Jun 15;17(1):221.

- Stein AG, Johnson BN. The “favorite person” in borderline personality disorder: A content analysis of social media posts. Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationships. 2025 Jun 30;19(1):94-115.

- Jeong H, Jin MJ, Hyun MH. Understanding a mutually destructive relationship between individuals with borderline personality disorder and their favorite person. Psychiatry investigation. 2022 Dec 22;19(12):1069.

- Story GW, Smith R, Moutoussis M, Berwian IM, Nolte T, Bilek E, Siegel JZ, Dolan RJ. A social inference model of idealization and devaluation. Psychological Review. 2024 Apr;131(3):749.

- O’connell B, Dowling M. Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing. 2014 Aug;21(6):518-25.

- Flechsig A, Bernheim D, Buchheim A, Domin M, Mentel R, Lotze M. One year of outpatient dialectical behavioral therapy and its impact on neuronal correlates of attachment representation in patients with borderline personality disorder using a personalized fMRI task. Brain Sciences. 2023 Jun 28;13(7):1001.

- Meyer D. Neuroplasticity as an explanation for the attachment process in the therapeutic relationship. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dixie-Meyer/publication/261700116_Neuroplasticity_as_an_Explanation_for_the_Attachment_Process_in_the_Therapeutic_Relationship/links/0f317537c3d27395f2000000/Neuroplasticity-as-an-Explanation-for-the-Attachment-Process-in-the-Therapeutic-Relationship.pdf. 2011. Accessed August 28, 2025.

- Dansby Olufowote RA, Fife ST, Schleiden C, Whiting JB. How can I become more secure?: A grounded theory of earning secure attachment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2020 Jul;46(3):489-506.

- Vogt KS, Norman P. Is mentalization‐based therapy effective in treating the symptoms of borderline personality disorder? A systematic review. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2019 Dec;92(4):441-64.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox