Rejection Sensitivity: Hidden Attachment Origins and How to Heal

Rejection hurts – whether it’s an unsuccessful job interview, a turned down date, or exclusion from other people’s plans, everybody has felt its sting.

For some people, rejection hurts more than it does for others. If you feel intensely afraid of rejection and deeply hurt when you face it, you may have rejection sensitivity.

Rejection sensitivity is not a diagnosis, but a descriptive term for someone who has more pronounced reactions to rejection. It does, however, have associations with other diagnoses, and is especially common in ADHD1. You might hear it called “rejection sensitive dysphoria“, or RSD, in this context.

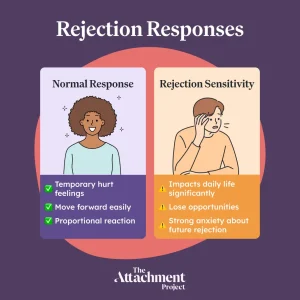

Some level of sensitivity to rejection is expected – we are, after all, social beings whose survival often depends on acceptance. This is why rejection can make us feel embarrassed, ashamed, or angry – but difficulty managing anxiety about rejection, regulating emotional responses to rejection, and frequent triggers for rejection could be signs of heightened rejection sensitivity.

In this article, we’ll talk in depth about what rejection sensitivity really is, how to tell if you have it, how it could relate to your attachment style and manifest in your relationship, and techniques to better manage your feelings around rejection.

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

What is Rejection Sensitivity?

Rejection sensitivity is not a categorical concept – it is not a yes or no box you can check to say whether you do or don’t have it. Instead, like our personality traits, it exists on a spectrum. Studies have found that most people have a low-medium baseline level of rejection sensitivity: in one study based in the USA, 68% of the 685 participants scored between 5 and 12.2, where 36 is the maximum score2.

The test that they took is called the Adult Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (A-RSQ). The A-RSQ is a widely accepted measurement tool for rejection sensitivity, and it factors in both anxiety about rejection and expectation of rejection.

Psychologists may use tools like this alongside your personal history to understand whether you experience high rejection sensitivity.

Rejection sensitivity manifests not only in your dating life, but in all domains. When you are highly sensitive to rejection, any perceived rejection at work, home, or within friendships could be a trigger.

For example, when undergraduate students with ADHD diagnoses were interviewed about rejection sensitivity, many of them reported putting off assignments or self-sabotaging by submitting work that they knew was below their abilities3. The expectation of rejection was often more damaging than the rejection itself, with one participant saying:

“I just get myself out of the situation where the rejection might come, just to avoid it.”

This rejection avoidance can cause us to miss out on opportunities for work, friendship, and other experiences, which can negatively impact our overall quality of life.

Signs You May Experience Rejection Sensitivity

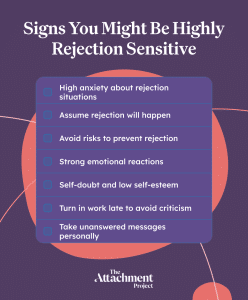

Typically, if you relate to any of the following, you may have high rejection sensitivity:

- High anxiety about situations that could lead to rejection.

- A tendency to assume any situation that could lead to rejection will lead to rejection.

- Aversion to possible exposure to rejection – not taking risks.

- Strong emotional reactions to rejection.

- Self doubt and low self-esteem.

People with rejection sensitivity report that they experience3:

- Turning in work late or below standard because rejection is anticipated anyway.

- Assuming that messages going unanswered means rejection.

- Ruminating on possible rejection.

- Feeling “lonely”, “friendless”, or “unlovable”.

- Feeling undeserving of good grades or job prospects.

- Feeling disconnected from social interactions as a way of self-protection.

- Strong bodily sensations in response to rejection.

When differentiating between rejection sensitivity and realistic concerns, the most important question to ask is: “how does this impact my life?” – if your life is measurably worse due to rejection sensitivity because you lack confidence, lose opportunities, and struggle in interactions with others, then you may be experiencing a higher level of rejection sensitivity than you can manage.

Rejection Sensitivity vs. Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria

The term “RSD” was initially created to describe the specific manifestation of rejection sensitivity in ADHD4. The core features of RSD include:

A clear rejection trigger before an intense mood shift, like:

- Another person’s withdrawal of affection or respect.

- Teasing by another person.

- Criticism, even when intended constructively.

- Self-rejection caused by a perceived failure to live up to their own expectations.

Additional characteristics:

- The mood shift is instant, occurring immediately after the trigger.

- Severe depression (if mood is internalized) or rage (if mood is externalized).

RSD was also associated with symptoms beginning in childhood and an indescribable physical pain when experiencing rejection.

This definition of RSD grew from existing research on rejection sensitivity, so there can be significant crossover. RSD can be understood as the most intense form of rejection sensitivity, but since neither are official diagnoses, there is no diagnostic criteria to formally distinguish one from the other.

The Neuroscience and Attachment Origins of Rejection Sensitivity

Earlier, we touched on the idea that we are social beings who need acceptance to survive; this is the evolutionary perspective on how we process rejection5. In the evolutionary environment, we had to work together to survive – so rejection from the group could threaten our lives.

The social functionist theory suggests that emotions exist to motivate us toward a new course of action for survival6. Through this lens, we can see that the embarrassment or shame caused by rejection could drive us to repair our relationships with the rejector and/or be more careful in the future. If we feel angry, we may be driven to fiercely protect ourselves or challenge our place in a social hierarchy.

So, rejection sensitivity could be an overactive form of this natural evolutionary process.

This response to rejection is so deeply ingrained that scientists are able to see it in the brain. When experiencing rejection, brain regions involved in processing emotional content and cognitive control are both active, no matter where you fall on the spectrum of rejection sensitivity7.

People with high rejection sensitivity have been found to have less activation in the frontal cortex, where our higher level cognitive functions happen – suggesting that rejection sensitivity comes from an absence of regulation, rather than a heightened neural response to rejection itself. Incidentally, low activation in the prefrontal cortex is also implicated in ADHD8.

Another study found that poor communication between the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, implicated in mood regulation, and the prefrontal cortex could be involved in rejection sensitivity9, 10.

However, in the debate between nature and nurture we almost always have to look at both sides. While our rejection sensitivity could be influenced by neurobiology, our early childhood experiences play a role too.

Early Attachment Rejection Experiences

Experiencing rejection early in life has been associated with the development of rejection sensitivity. Research has found that children who are mistreated are more likely to develop rejection sensitivity, especially in cases of emotional mistreatment11.

Children raised with an authoritarian parenting style, characterized by high expectations, strict rules, and an absence of warmth in their parental relationships are also more likely to become rejection sensitive young adults12.

Your early experiences of friendships can also play a role: in one prospective study, children’s ratings of peer support at age 9 were significantly associated with their rejection sensitivity at age 1213. This means that if you experienced difficulty with friendships in school, you might be more likely to develop rejection sensitivity in adolescence.

Internal Working Models of Rejection

Our early experiences give us a template for what to expect in later life. In attachment theory, this is called our internal working model. Your internal working model influences how you think and feel about yourself, the people around you, and the wider world.

If you experience repeated rejection in infancy and childhood, you may develop an internal working model that expects rejection from others. You may even learn to reject yourself. These patterns can become a self-fulfilling prophecy: you feel as though people will reject you, so you act in ways that ensure they do. An example of this would be not applying for a job because you think you’ll be rejected anyway, or not talking to a group of people because you assume you won’t be welcomed.

This, in turn, perpetuates your assumptions that you’ll be rejected. It can be a nasty cycle, and this is how these ideas can become deeply ingrained without intervention. However, it is possible to break the cycle – we’ll talk more about ways to manage rejection sensitivity soon.

How Rejection Sensitivity Manifests Across Attachment Styles

The same early experiences that lead to rejection sensitivity could also lead to insecure attachment styles, which develop when a caregiver is either consistently or unpredictably unable to meet a child’s needs.

It’s not so surprising, then, that researchers do find associations between attachment styles and rejection sensitivity14. In one study, attachment styles were able to explain almost 14% of the variance of rejection sensitivity – secure attachment was the only one related to lower rejection sensitivity, while avoidant, anxious, and fearful attachment styles all predicted higher levels of rejection sensitivity12. This isn’t the only study to have made these findings – so, how does your own attachment style link to rejection sensitivity15?

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

Rejection Sensitivity and Anxious Attachment

An anxious attachment develops when a caregiver is inconsistently responsive – because methods of gaining attention only work some of the time, infants learn to do everything they can to get it. In adulthood, high attachment anxiety can manifest as a fear of abandonment and “clingy” behavior when the relationship feels threatened.

A study on the relationship between rejection sensitivity and attachment styles high in anxiety (both anxious and fearful attachment styles) found that anxious and fearful attachment styles are both linked to high rejection sensitivity, worry, and low self-esteem16. Worry and low self-esteem were themselves associated with high rejection sensitivity, meaning they may play their own role in its relationship with attachment anxiety.

Studies have even found that rejection leads to higher brain activity in regions associated with rejection pain for individuals with high attachment anxiety17. This means that people with anxious attachment styles may be particularly prone to feeling the pain of social rejection.

When they feel rejected, people with anxious attachment styles tend to make extra efforts to regain the connection. They may call or text often, and find it hard to give their partner some space. This can push their partner further away, particularly when their partner has an avoidant attachment style – leading to the self-fulfilling prophecy of rejection.

Rejection Sensitivity in Avoidant Attachment

The same study on brain activity found that regions associated with rejection distress are significantly lower following rejection in people with attachment avoidance – so why is attachment avoidance still related to rejection sensitivity?

Attachment avoidance develops when a caregiver is consistently unresponsive to the infant’s needs. The infant learns that nothing they do to gain attention will work, so they learn to ignore their need for care from others and become very self-reliant.

Their internal working model for rejection is that it is inevitable – they come to expect rejection in any scenario, and their avoidant behavior could lead to another self-fulfilling prophecy. Their brains could have decreased responses to rejection due to habituation, which is the process where a repeated experience produces less intense responses as you become used to it.

However, remember that rejection sensitivity is not only measured by someone’s response to rejection, but by their expectation of it. Perhaps, because people with avoidant attachment styles are so used to rejection, their high rejection expectancy plays a strong role in their rejection sensitivity scores.

Rejection Sensitivity in Fearful-Avoidant Attachment

What happens when someone has both high attachment avoidance and high attachment anxiety?

This is sometimes linked with disorganized attachment in infants, which stems from fear of the caregiver, though there’s some debate around whether infant disorganized attachment and adult fearful-avoidant attachment are as congruent as other attachment styles.

Because fearful attachment styles are high in both avoidance and anxiety, people with fearful attachment styles can move between the two and may react quite unpredictably to a relationship trigger. Since both avoidance and anxiety are associated with rejection sensitivity, it’s no surprise that fearful attachment styles also tend to score highly.

Rejection Sensitivity in Dating and Relationships

Dating can already be difficult, and rejection sensitivity can make it even harder. If you anticipate rejection, you might find it difficult to pursue people you’re interested in. If you’re dating online, you may find that you match with people only to never start a conversation, or you communicate online but struggle to commit to meeting in person.

Once you’re in a relationship, rejection sensitivity can still present hurdles. Some people with rejection sensitivity say that changes in their partner’s tone, attention, or expected responses can cause them to spiral. If you don’t feel able to communicate these difficulties, they could continue to create distance in your relationship and contribute to conflict later down the line.

Digital communication could make rejection sensitivity even more problematic. There is a constant sense of availability which enables us to send a message at any time and anticipate a quick response – only this often doesn’t happen. The sense of availability is not a reality, and there are any number of reasons someone might not respond to a message. However, people with rejection sensitivity might take the lack of a quick response personally3.

Since rejection sensitivity has such a widespread impact on relationships, it’s understandable that research has found that people high in rejection sensitivity tend to have lower levels of relationship satisfaction and feelings of closeness18. They may even be more prone to jealousy, self-silencing, and sexual compulsivity.

START YOUR HEALTHY DATING JOURNEY

How Partners Experience Your Rejection Sensitivity

The impact of rejection sensitivity could be tough on your partner, even if they don’t struggle with rejection sensitivity themselves. If you experience self-sabotage and self-rejection, this could lead to behaviors that ultimately reject your partner. For example, if you don’t plan dates with your partner in case they don’t like your plans, your partner may feel that you aren’t interested in spending quality time with them. Because of this, they may highlight that they need more from the relationship or withdraw from it, leading you to feel rejected by them.

This is another example of how rejection sensitivity can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, but we want to focus on the effect on the partner here: by preparing for rejection from them, you might actually be rejecting them.

If you think your rejection sensitivity is affecting your partner, try being open with them about what you’re experiencing. This might be difficult, but a shared understanding can lead to fewer conflicts and a deeper connection.

Even though your partner can help you to manage rejection sensitivity, it’s important to learn how to manage it yourself – and this starts with recognition.

Recognizing Your Rejection Sensitivity Triggers

Everybody has different triggers, although they might follow similar patterns. For example, some people report that feeling like they’re missing something in a conversation, having someone change their tone with them, or a lack of physical touch can trigger their rejection sensitivity. Here are a few more examples of triggers in different contexts:

Dating: your date is late, spends time on their phone while with you, or they ghost. These are understandably upsetting for anyone, but if you have rejection sensitivity you may take it much harder.

At work: your colleagues are too busy to help you, you receive negative feedback, or colleagues talk about plans they made without you. This could lead to withdrawal and isolation at work, which can impact your professional development.

Online: your messages are left on “read”, or unopened even though you can see the recipient is online, or your friends post pictures of plans you weren’t part of. There are lots of reasons someone might not be quick to respond – try turning read receipts and online status off where you can. Remember that there are also lots of potential explanations if you see a post that seems to exclude you, and try not to jump to conclusions.

To recognize triggers, first you have to be able to recognize how rejection feels. It can feel different for everybody – what are the physical sensations, thoughts, and emotions that come through? When you identify that feeling, think about what might have caused it. It might help to keep a list of potential triggers so that you can find patterns.

This might also help you to recognize the severity of the rejection – when you step back and read your triggers from a calmer perspective, you might get a better sense of whether your reaction is proportional.

Developing Rejection Resilience: Healing Strategies

Some kinds of therapy are better suited to rejection sensitivity than others. Since cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can target automatic negative interpretations, it could be used to help individuals with rejection sensitivity to change the way they see their interactions19. This works primarily through cognitive reframing, the practice of considering other angles and shifting your perspective on worrisome thoughts. CBT also involves identifying feelings, so it can help with noticing rejection triggers too.

If you’re particularly concerned by anxiety around rejection, a graded exposure therapy could help. These are often used for phobias, including social anxiety20. Graded exposure therapy involves creating a hierarchy of challenging situations, from the least scary (0%) to the most (100%), often in increments of 10%. Then, with a therapist’s help and guidance, you can work your way from the bottom of the ladder to the top. This can help you to slowly get used to the idea and the feeling of rejection, but it’s important to work through it with a professional who can help you with the challenging thoughts and feelings that might come alongside it.

Self-compassion is another excellent tool for managing rejection sensitivity, especially if you’re prone to self-rejection. Treat yourself as if you are your own best friend – forgive yourself for the times you’ve felt you made mistakes. Give yourself time and appreciate all of your efforts, and remember that self-compassion is like a muscle: the more you practice it, the stronger it will become. If you struggle with self-compassion, compassion-focused therapy could help you.

Therapy isn’t necessarily the right route for everyone all of the time, and that’s okay. Building a more secure attachment base and collecting a practical toolkit can help you to work on rejection sensitivity in your own time.

Building Earned Secure Attachment

Since secure attachments are related to rejection resilience, working towards feeling secure in your relationships could theoretically help you to feel secure in rejection. Attachment-focused therapy can help you to learn more about your attachment style and work towards security, but if therapy isn’t for you, you can start by learning more about your attachment style and how it shows up in your life.

When your attachment style shifts, there are changes in your brain to match – this is called neuroplasticity21. Neuroplasticity enables your neurons to reorganize and change your way of thinking; the more you practice a certain thought or behavior, the stronger the neuronal connections become, and the easier it is for those thoughts or behaviors to come automatically.

Neuroplasticity comes with time, patience, and repetition. Experiencing secure relationships with others can be one of the best ways to promote a learned secure attachment, but practicing emotional regulation and cognitive reframing in all triggering situations can help. Here are a few more practical tools for managing rejection sensitivity:

Practical Tools for Managing Rejection Sensitivity

Mindfulness techniques

We know, mindfulness is recommended all the time – but we promise it’s for good reason. The latest research continues to find that practicing mindfulness benefits our mood, psychological wellbeing, and emotional regulation22. That last one is key to building rejection resilience.

Cognitive-behavioral strategies

When faced with a trigger, reframing your thoughts can help you to re-evaluate the situation. Take the example of someone leaving your message on read – your automatic thought might be that they weren’t interested in replying, but what other possibilities could there be? Might they have been interrupted, or busy when they opened the message? Might they have been somewhere with bad signal? Don’t try to work out the answer, just hold the less hurtful possibilities in mind until you hear back.

Body-based practices

When rejection sensitivity is triggered, people describe all kinds of uncomfortable, sometimes physically painful sensations. You might notice the stress response activate, characterized by a faster heart rate, heavier breathing, and sweating. You can counteract this by controlling your breathing – try learning some breathing techniques like box breathing (in for 4 seconds, hold for 4, out for 4, hold for 4).

Emotional regulation skills

Practicing emotional regulation can help you to respond differently to rejection. The first stage is to practice noticing your strong emotions, then use countering techniques like breathing exercises and mindfulness to bring your emotions down.

Practicing communication

If your rejection sensitivity is getting in the way in your friendships, relationships, or workplace, it may help to find a way to communicate this to people you trust. For example, telling your partner that you don’t plan dates in case they won’t like them can help you to problem solve together – maybe your partner can give you some ideas, or you can create a date raffle together. Communicating your triggers can also help you to set boundaries; for example, if your friends discuss plans you can’t attend in front of you, you could let them know how it makes you feel and ask them to discuss their plans separately.

Whichever tools you choose, remember that all of them take time and practice to get good at, like any skill. Keep self-compassion if it doesn’t click right away – every time you try is one step closer.

Rejection Sensitivity and Mental Health Conditions

While these tools can help, it’s important for us to discuss that rejection sensitivity is often linked to another condition.

We have already touched on its relevance to ADHD and how a difference in brain structures related to cognitive control could lead to rejection sensitivity. However, the link between rejection sensitivity and ADHD is more complex. Children with ADHD, like other neurodivergent children, can grow up feeling like they don’t fit in. They think differently and may act differently to other children, which can lead them to experiencing rejection often and from an early age. It’s natural, then, that children with ADHD can grow up extra wary and sensitive to rejection, compounding on their possible predisposition to rejection sensitivity.

Rejection sensitivity is also strongly implicated in borderline personality disorder (BPD)23. This is likely due to the intense fear of abandonment present in BPD, but the same process that exacerbates rejection sensitivity in ADHD could be at work here too; people with BPD may be more likely to experience rejection from others, which may lead to even stronger rejection sensitivity.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, rejection sensitivity is also linked to social anxiety24. Social anxiety, like rejection sensitivity, involves a fear of future social situations and a negative appraisal of past ones. This can result in the same avoidance tactics to escape feeling rejected or judged negatively, which leads to greater anxiety.

Depression is also related to rejection sensitivity, likely due to an overall tendency to see things negatively25. Again, if you avoid activities because of depression, you may be more likely to feel anxious about them in the future. Cognitive reframing can be particularly helpful if you find negative thought patterns are causing problems.

Rejection sensitivity can be complicated – if you feel you have rejection sensitivity linked to another condition, it can help to look at the whole picture.

Conclusion

Rejection sensitivity is a tough challenge, but one that can be overcome. It takes time, practice, and maybe a little experimentation to find out which tools are the most effective for you. Remember that rejection sensitivity is a normal reaction to abnormal circumstances – the environments that led you to develop an insecure attachment style could also have nurtured an internal working model that expects rejection.

Everybody feels hurt by rejection, so it’s not always something that needs to be addressed. If it’s negatively affecting your life often, however, you may benefit from exploring rejection sensitivity further. Learning more about rejection sensitivity, your attachment style, and practical tools or therapies to move towards attachment security can help you on your way to more fulfilling relationships with less fear of rejection.

FAQs About Rejection Sensitivity

Is rejection sensitivity a symptom of ADHD?

Yes, rejection sensitivity is a symptom of ADHD. It’s thought to be the result of both neurological disposition and social experience.

What’s the difference between normal feelings of rejection and rejection sensitivity?

If your reactions and fear of rejection are so strong that it’s negatively affecting your life, e.g. by preventing you from doing things you want to do, then you may have rejection sensitivity. There is no set criteria as rejection sensitivity is not a diagnosis.

Can rejection sensitivity be cured?

Rejection sensitivity is not a diagnosis, but it can be worked on and managed through emotional regulation skills, cognitive reframing, and mindfulness.

Is a rejection sensitivity test accurate?

The Adult-Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (A-RSQ) and some of its modified versions have good scores of accuracy and reliability. Other rejection sensitivity tests may not be as accurate.

Is rejection sensitivity a trauma response?

Rejection sensitivity is not necessarily a trauma response, although it may relate to childhood mistreatment. This is not the only explanation for rejection sensitivity.

What’s the connection between borderline personality disorder and rejection sensitivity?

Fear of abandonment, a core element of BPD, is strongly related to rejection sensitivity. People with BPD may also be more likely to experience painful rejection, which exacerbates rejection sensitivity.

Why is my rejection sensitivity so high?

Rejection sensitivity could be high for a number of reasons, including attachment style, low self-esteem, and an association with conditions like ADHD, depression, BPD, and social anxiety.

Are avoidants sensitive to rejection?

People with avoidant attachment styles score highly on rejection sensitivity.

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

References

-

Müller V, Mellor D, Pikó BF. Associations between ADHD symptoms and rejection sensitivity in college students: exploring a path model with indicators of mental well-being. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2024 Nov;39(4):223-36.

-

Berenson KR, Gyurak A, Ayduk Ö, Downey G, Garner MJ, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Rejection sensitivity and disruption of attention by social threat cues. Journal of research in personality. 2009 Dec 1;43(6):1064-72.

-

Rowney-Smith A, Sutton B, Quadt L, Eccles JA. The lived experience of rejection sensitivity in ADHD-a qualitative exploration. medRxiv. 2024 Nov 18:2024-11.

-

Dodson WW, Modestino EJ, Ceritoğlu HT, Zayed B. Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Case Series. Neurology. 2024;7:23-30.

-

Kawamoto T, Nittono H, Ura M. Trait rejection sensitivity is associated with vigilance and defensive response rather than detection of social rejection cues. Frontiers in psychology. 2015 Oct 2;6:1516.

-

Keltner D, Sauter D, Tracy JL, Wetchler E, Cowen AS. How emotions, relationships, and culture constitute each other: Advances in social functionalist theory. Cognition and Emotion. 2022 Apr 3;36(3):388-401.

-

Kross E, Egner T, Ochsner K, Hirsch J, Downey G. Neural dynamics of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007 Jun 1;19(6):945-56.

-

Salavert J, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Moreno-Alcázar A, Caseras X, Palomar G, Radua J, Bosch R, Salvador R, McKenna PJ, Casas M, Pomarol-Clotet E. Functional imaging changes in the medial prefrontal cortex in adult ADHD. Journal of attention disorders. 2018 May;22(7):679-93.

-

Drevets WC, Savitz J, Trimble M. The subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in mood disorders. CNS spectrums. 2008 Aug;13(8):663.

-

Sun J, Zhuang K, Li H, Wei D, Zhang Q, Qiu J. Perceiving rejection by others: Relationship between rejection sensitivity and the spontaneous neuronal activity of the brain. Social Neuroscience. 2018 Jul 4;13(4):429-38.

-

Gao S, Assink M, Bi C, Chan KL. Child maltreatment as a risk factor for rejection sensitivity: a three-level meta-analytic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2024 Jan;25(1):680-90.

-

Erozkan A. Rejection sensitivity levels with respect to attachment styles, gender, and parenting styles: A study with Turkish students. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal. 2009 Feb 1;37(1):1-4.

-

Araiza AM, Freitas AL, Klein DN. Social-experience and temperamental predictors of rejection sensitivity: A prospective study. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2020 Aug;11(6):733-42.

-

Natarajan G, Somasundaram CP, Sundaram KR. Relationship between attachment security and rejection sensitivity in early adolescence. Psychological Studies. 2011 Dec;56:378-86.

-

Ishaq M, ul Haque MA. Attachment styles, self-esteem and rejection sensitivity among university students. Pakistan Journal of Psychology. 2015 Dec 30;46(2).

-

Khoshkam S, Bahrami F, Ahmadi SA, Fatehizade M, Etemadi O. Attachment style and rejection sensitivity: The mediating effect of self-esteem and worry among Iranian college students. Europe’s Journal of Psychology. 2012 Aug 29;8(3):363-74.

-

DeWall CN, Masten CL, Powell C, Combs D, Schurtz DR, Eisenberger NI. Do neural responses to rejection depend on attachment style? An fMRI study. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2012 Feb 1;7(2):184-92.

-

Mishra M, Allen MS. Rejection sensitivity and romantic relationships: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences. 2023 Jul 1;208:112186.

-

Normansell KM, Wisco BE. Negative interpretation bias as a mechanism of the relationship between rejection sensitivity and depressive symptoms.

-

Veale D. Treatment of social phobia. Advances in psychiatric treatment. 2003 Jul;9(4):258-64.

-

Meyer D. Neuroplasticity as an explanation for the attachment process in the therapeutic relationship. Recuperado de https://counselingoutfitters. com/vistas/vist as11/Article_52. pdf. 2011.

-

Aldbyani A. The effect of mindfulness meditation on psychological well-being and mental health outcomes: a cross-sectional and quasi-experimental approach. Current Psychology. 2025 Feb 3:1-0.

-

Bungert M, Liebke L, Thome J, Haeussler K, Bohus M, Lis S. Rejection sensitivity and symptom severity in patients with borderline personality disorder: effects of childhood maltreatment and self-esteem. Borderline personality disorder and emotion dysregulation. 2015 Dec;2:1-3.

-

Lin Y, Fan Z. The relationship between rejection sensitivity and social anxiety among Chinese college students: The mediating roles of loneliness and self-esteem. Current Psychology. 2023 May;42(15):12439-48.

-

Normansell KM, Wisco BE. Negative interpretation bias as a mechanism of the relationship between rejection sensitivity and depressive symptoms. Cognition and Emotion. 2017 Jul 4;31(5):950-62.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox