What Is Attachment Theory?

Attachment theory is a scientifically-backed understanding of relationships and personal development. At The Attachment Project, our goal is to make the science of attachment theory accessible to all. We have compiled an overview of what attachment theory is, its implications for our relationships, and its influence on other psychological fields.

In this page you’ll find:

- The foundation of attachment theory

- The attachment classification system

- The stages of attachment

- The emotional skills we learn from attachment

- Relationships from an attachment perspective

- Brief overview of our guidelines for attachment classification

- Influence on other fields and future directions

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

The History of Attachment Theory

Attachment theory has a long and detailed history, influenced heavily by Freud’s psychoanalytic theory. The following timeline of attachment theory lays out just a few key moments in the development of attachment theory:

1935

Lorenz writes about imprinting in geese, where rapid attachment bonds are formed after birth: attachment is understood to be innate and instinctive.

1958

Bowlby publishes the first paper formally outlining attachment theory, “The Nature of the Child’s Tie to his Mother”, rejecting the idea that emotional attachment comes secondary to resource provision.

1961

Harlow finds that baby monkeys given two “mothers” – one made with wire that provides food, and one made with soft cloth that doesn’t provide food – will choose to seek comfort from the soft mother when stressed. This supported Bowlby’s ideas that emotional attachment is more significant than providing food.

1963

Ainsworth presents her findings on attachment based on observations in Uganda: infants were classified as “securely attached”, “insecurely attached”, and “not yet attached”, and secure attachment was linked to mother’s sensitivity.

1964

Schaffer & Emerson identified 4 stages of attachment formation in infants up to 18 months old.

1970

Ainsworth publishes the Strange Situation classification system, a laboratory test that classifies infants up to 18 months old as “secure”, “insecure-avoidant”, and “insecure-resistant”.

1986

Main & Solomon identify infants whose behavior doesn’t fit in with the 3 organized attachment classifications. These are classified as “disorganized”.

1987

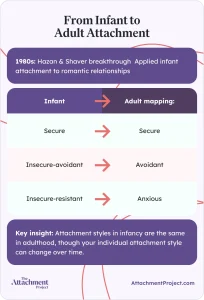

Hazan & Shaver extend attachment theory to adult romantic relationships, finding that adult attachment styles map onto the 3 organized infant attachment styles.

1998

Brennan, Clark & Shaver produce the Experiences in Close Relationships scale, a widely used adult attachment measure which classifies attachment on the domains of anxiety and avoidance, resulting in 4 possible attachment types.

Bowlby’s Attachment Theory

Bowlby’s attachment theory suggests that attachment bonds are innate, healthy (rather than signs of dependence), and activated by behavior1. When a child’s immediate need for a secure attachment bond is not met, the child feels threatened and will react accordingly, such as by crying or calling out for their caregiver. Moreover, if the need for a stable bond is not met consistently, the infant can develop social, emotional, and even cognitive problems2.

Ainsworth and Attachment Theory: The Strange Situation

Mary Ainsworth worked closely with Bowlby, and crucially contributed to attachment theory with the concept of a secure base1. In her view, a child needs an established secure base in the form of a caregiver in order to venture into the world around them and safely explore.

The Strange Situation is perhaps the most well-known of Ainsworth’s main contributions3. The study was designed to look at the association between attachment and infants’ exploration of their surroundings.

Children between the ages of 12 and 18 months from a sample of 100 typical American families were observed in the Strange Situation.

A small room was set up with a one-way glass window designed to covertly observe the actions of the child. The room was filled with toys, and at first, it was just the infant and their mother.

The Strange Situation consisted of eight steps, each of which lasted approximately 3 minutes:

- Mother and infant alone.

- A stranger enters the room.

- The mother leaves the baby and stranger alone.

- The mother returns.

- The stranger leaves.

- The mother leaves and the child is left alone.

- The stranger returns.

- Mother returns and the stranger exits.

The Attachment Classification System

From the Strange Situation, Ainsworth developed the Strange Situation Classification, which is the cornerstone of how we categorize attachment styles today. Ainsworth distinguished three attachment styles:

- Secure – the child displays distress when separated from the mother, but is easily soothed and returns their positive attitude quickly when reunited with them.

- Resistant – the child displays intense distress when the mother leaves but resists contact with them when reunited.

- Avoidant – the child displays no distress when separated from their mother, as well as no interest in the mother’s return.

Disorganized Attachment

Ainsworth’s Strange Situation was incredibly helpful in categorizing infant attachment, but Main and Solomon found that a small percentage (around 10%) of infants were difficult to classify into one of the 3 attachment styles4. They showed unusual behaviors like hand-slapping, signs of fear, or apparent dissociation. These behaviors usually appeared during the reunion phase, but could appear at any time throughout the experiment and usually resolved quickly.

To describe these infants, Main and Solomon introduced the disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. This attachment pattern was intended to represent dysregulation in the attachment system, rather than a 4th style classification. Fear in the caregiving environment, major separation, and low socioeconomic status are associated with the development of disorganized attachment. While trauma and abuse are common in disorganized attachment, neither are necessary for it to develop.

The Stages of Attachment

In 1960s Glasgow, psychologists Schaffer and Emerson studied babies and their attachments from birth to 18 months old5. Not only were they able to identify stages of attachment development, but they also found that infants were more likely to develop attachments to the caregivers who were the most sensitive to their needs versus the caregivers they spent the most time with.

The stages of attachment they identified were as follows:

Asocial Stage

0-6 weeks. Babies don’t distinguish between humans, although there is a clear preference for humans over non-humans. The infants form attachment with anyone who comes their way.

Indiscriminate Stage

6 weeks – 6 months. The bonds with their caregivers start to grow stronger. Infants begin to distinguish people from one another, but they do not yet have a fear of strangers.

Specific Attachment Stage

7+ months. This is when separation anxiety becomes prevalent, particularly from their main caregiver. Infants at this stage look for specific people for comfort.

Multiple Attachments Stage

10+ months. Attachment with the infant’s primary caregiver grows even stronger. The infant is increasingly interested in creating bonds with others that are not their caregivers, such as siblings or grandparents.

The Conditions for Secure Attachment

To develop a secure attachment style, a child simply needs to know that their emotional needs will be reliably met. This doesn’t need to be perfect – one study found that a secure attachment could still develop when emotional responses were mismatched up to 70% of the time10. Rupture and repair is a normal part of healthy relationships, and it’s beneficial for infants to experience this in a safe, supportive environment.

On the other hand, the following experiences can lead to an insecure attachment to form during childhood:

- Drastic inconsistency: Caregivers might swing rapidly from absence to over-attentiveness. Their responses can be unpredictable, and the child learns that over-activating their attachment system can eventually result in their emotional needs being met. This can lead to attachment anxiety.

- Rejection or neglect: Caregivers are generally absent or unable to meet the infant’s emotional needs. The infant learns to suppress expressing their emotional needs – even though they do feel distressed, their emotional suppression can be mistaken for independence. This can lead to attachment avoidance.

- Sense of fear: A sense of fear can come from anything frightening in the infant’s environment, including a caregiver’s unpredictable behavior or sudden separation. In infants, this is associated with attachment disorganization, although infants with this classification will likely default to an organized attachment style most of the time.

Learning Relationship Skills From Attachment

Our main attachment relationships, especially those in our earliest stages of life, have a unique influence on how we handle other relationships later on6. An important role that these attachment relationships have is to teach us healthy affect regulation.

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

Affect regulation, or emotion regulation, is the extent to which we can experience emotions and process these in a healthy way.

Emotion regulation is especially important when we encounter negative experiences. As infants, these negative experiences are a key opportunity to cultivate this skill. It is also in these moments that we learn how, or to what extent, we can rely on our caregivers to support us7. Thus, if we don’t feel protected or understood by our caregivers, we can learn that they are not reliable sources of safety or love.

Moreover, we learn emotion regulation and relationship skills directly through our caregivers’ behaviors. Basically, we mirror our caregivers’ actions; for instance, if we notice that our cries bring about distress in our caregiver, we feel greater distress in return8. Thus, an infant develops a sense of self by assessing their impact on their surroundings. If their caregivers consistently react to the child negatively or neglect them in some way, the child will develop a distorted view of themselves and their capacity to interact with their environment.

Relationships Through the Lens of Attachment Theory

Today, attachment theory is regularly applied to a vast array of relationships – but this was not always the case. In the 1980s, Cindy Hazan and Philip Shaver introduced their views on attachment, arguing that its classification system could be applied to romantic relationships as well as the original caregiver-child format6. Their argument relied on the premise that relationships and love take many shapes and forms, and an attachment reaction typically follows.

With this perspective in mind, we can begin to see how attachment is not a static aspect of ourselves – it fluctuates depending on a specific relationship and situation. While we do have our first encounter with an attachment relationship at birth, with our caregivers, this is not the only relationship that will influence how we relate to others. From childhood onwards, the people closest to us all have an impactful role in our attachment style development.

What Is an Attachment Bond?

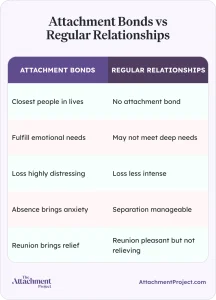

An attachment bond is one that we establish with the closest people in our lives, typically our caregivers, close family, or intimate partners.

Therefore, not every relationship we have will have an attachment bond. Instead, these bonds form in the relationships with people that fulfill our emotional needs. Losing an attachment bond is a highly distressing experience, and we’ve likely all experienced anxiety and sadness in the absence of somebody important to us.

This loss can feel very different depending on the type of relationship and bond that was developed. On the flip side, reuniting with an attachment figure after some time apart can bring about immense happiness and joy, and even a sense of relief.

The Anxious-Avoidant Spectrum

One popular way of measuring adult attachment is through Brennan, Clark & Shaver’s Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR)9. This conceptualizes attachment on 2 domains: attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance.

Since you can be high or low on both domains, the ECR gives 4 possible attachment styles. Three of these attachment styles map onto the 3 that were suggested by Hazan & Shaver (secure, anxious, and avoidant), which in turn mapped onto infant attachment styles. The fourth attachment style identified by the ECR acts as a combination of anxious and avoidant. Although this attachment style shares some characteristics with disorganized attachment, it doesn’t technically map onto Main & Solomon’s fourth infant attachment style – more on this coming up.

Our Classification of Attachment

At The Attachment Project, our work is grounded in scientific understanding. We use an online version of the ECR as a measure of attachment, resulting in the following 4 possible attachment styles:

Secure Attachment

Secure attachment is characteristic of people who easily trust others. These individuals are attuned to their own emotions and can easily attune to those of others. They are comfortable with intimacy and can easily communicate their thoughts and feelings.

The secure attachment is characterized by the ability to:

- Handle conflict calmly

- Feel comfortable both in relationships and on your own

- Differentiate thoughts from feelings

- Maintain a balanced sense of self and confidence

Anxious Attachment

Anxious attachment (also known as preoccupied or anxious-preoccupied attachment) can often be identified in people who essentially have an extra-sensitive attachment system. These individuals may struggle with hyperactivation of emotions, as well as hypervigilance for something going wrong in relationships and fear of abandonment.

Their attachment anxiety may stem from an inconsistent parent, who would be attentive at times yet misattuned most of the time.

The main signs of anxious attachment are the following:

- Catastrophic thinking, such as picturing things going very wrong, very easily

- A positive view of others, but a negative view of themselves

- Putting great effort into relationships, to the extent of self-sacrifice

- Immense difficulty with receiving criticism and rejection

Avoidant Attachment

Avoidant attachment (also known as dismissive or dismissive-avoidant attachment) is often present in individuals who tend to downplay their emotions or dismiss them completely. These people are typically highly independent and self-reliant, and their greatest fear is usually intimacy and vulnerability.

This attachment style can develop when caregivers were not emotionally attuned to their child or who were generally emotionally distant.

The main tell-tale signs of an avoidant attachment style are:

- Difficulty seeking support and admitting they need help

- Extreme self-reliance and independence

- A tendency to have a positive self-view yet a negative or critical view of others

- Maintaining or increasing distance when others try to connect emotionally

Fearful-Avoidant Attachment

Fearful-avoidant attachment (often also referred to as disorganized attachment, although there are some nuanced differences) is associated with childhood attachment insecurity and later negative relationships. The disorganized attachment style is characterized by inconsistent behaviors and difficulty trusting others.

Disorganized attachment can be identified by:

- Inconsistency and unpredictability in relationships and response to conflict

- Oscillating between avoidant and anxious behaviors

- Negative views of the self and others

- Struggles with intimacy and building trust in others

The Attachment Style Quiz

Our quiz, based on the ECR, is free and easy to complete – you can find out your attachment style in just 5 minutes.

There are other assessment alternatives you may want to opt for, which we’ve outlined in our blog post on commonly used attachment style tests. One such recommended measurement is the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), which must be conducted by a trained professional. If you want to further explore your attachment style, we suggest bringing the materials from our website (your quiz results and any relevant articles) to a mental health practitioner.

Discover your attachment style in just 5 minutes.

Receive your report straight away. Totally free!

Influence and Future Directions

Attachment theory has had a broad influence on other fields of study and contributed heavily to developmental psychopathology, especially the investigation of family relationships, and even the cross-cultural aspects of attachment.

At The Attachment Project, we seek to increase awareness of attachment theory and how it affects several aspects of everyday life.

For instance, there is a growing body of work on the association between organizational psychology and attachment theory psychology, aiming to understand how attachment impacts our behaviors and emotions in the workplace11. Scientists have also found links between attachment and a number of mental health concerns, such as eating disorders, addiction, ADHD, ASD, and issues with language development.

DISCOVER YOUR ATTACHMENT STYLE

Another interesting connection is to be found between attachment and early maladaptive schemas. Maladaptive schemas are, in a nutshell, limiting beliefs that are formed based on repeated negative experiences in early childhood.

Last but not least, attachment has a profound influence on many aspects of our personal relationships, such as jealousy, loneliness, and compassion.

We are eager to continue exploring the field and to help you, our readers, learn more about yourselves and gain the necessary insights to build the relationships and lives that align with your best selves.

Curious to learn more about your attachment style?

Get your digital Attachment Style Workbook to gain a deeper understanding of…

- how your attachment style developed

- how it influences different aspects of your daily life, such as your self-image, romantic relationships, sexual life, friendships, career, and parenting skills

- how you can use the superpowers associated with your attachment style

- how you can begin cultivating a secure attachment

- and more…

References

1. Bretherton I. The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. In Attachment theory 2013 Apr 15 (pp. 45-84). Routledge.

2. Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. American journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1982 Oct;52(4):664.

3. Ainsworth M.D.S., Wittig, B.A. Attachment and the exploratory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In: B.M. Foss, editor. Determinants of infant behavior. London: Methuen; 1969. p. 113-136. Vol. 4.

4. Duschinsky R. The emergence of the disorganized/disoriented (D) attachment classification, 1979–1982. History of psychology. 2015 Feb;18(1):32.

5. Schaffer HR, Emerson PE. The development of social attachments in infancy. Monographs of the society for research in child development. 1964 Jan 1:1-77.

6. Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. In Interpersonal development 2017 Nov 30 (pp. 283-296). Routledge.

7. Buckholdt KE, Parra GR, Jobe-Shields L. Intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation through parental invalidation of emotions: Implications for adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Journal of child and family studies. 2014 Feb;23(2):324-32.

8. Winnicott DW. Mirror-role of mother and family in child development. In Parent-infant psychodynamics 2018 Nov 9 (pp. 18-24). Routledge.

9. Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver P. Self-report measures of adult romantic attachment. Attachment theory and close relationships. 1998:46-76.

10. Tronick EZ, Gianino A. Interactive mismatch and repair: challenges to the coping infant. Zero to three. 1986 Feb.

11. Yip J, Ehrhardt K, Black H, Walker DO. Attachment theory at work: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2018 Feb;39(2):185-98.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox