Fearful Avoidant Triggers: Why Do I Feel Triggered By Both Closeness and Distance?

Published on September 23, 2025 Updated on September 24, 2025

Have you ever argued with a partner and felt torn between needing space and needing to keep them close? Maybe you’ve dated somebody whose responses to conflict were confusing like this, or you have a friend who acts the same way. This push-pull reaction to relationship difficulties is typical of the fearful-avoidant attachment style.

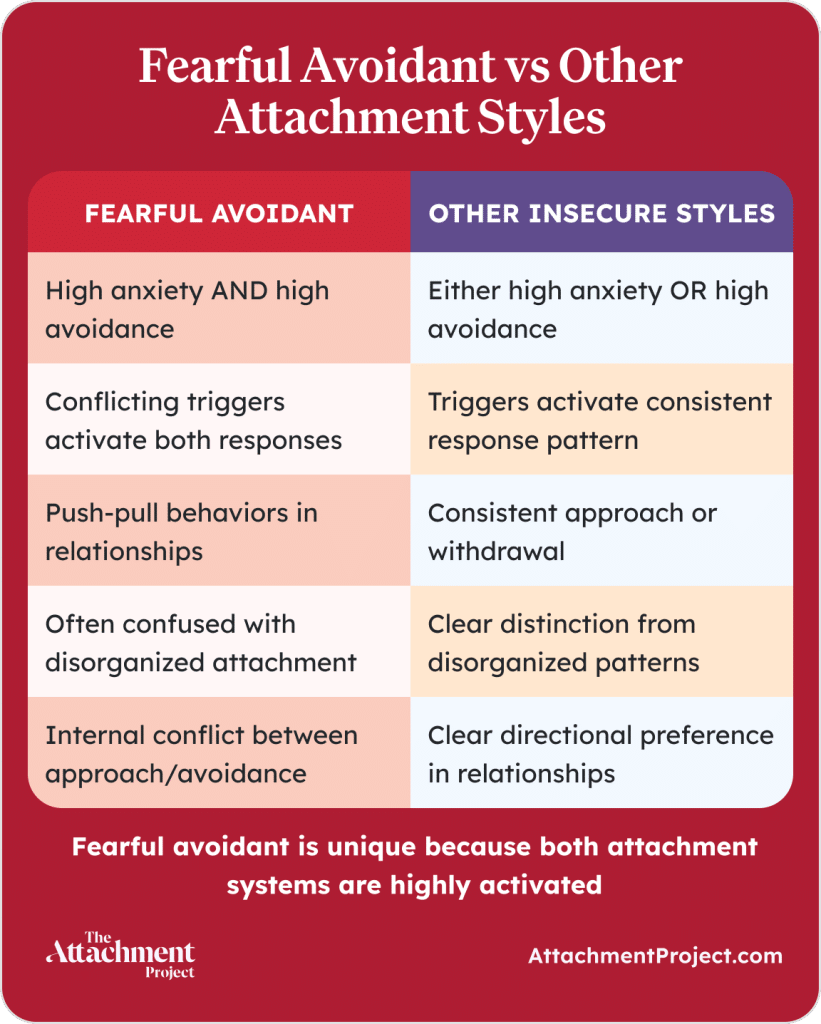

When you have a fearful-avoidant attachment style – which is also commonly referred to as a disorganized attachment style, due to their similarities – you might find yourself easily triggered within relationships and not sure what to do. You have strong drives for both approach and avoidance, so you find yourself caught in your own internal conflict when you’re facing conflict with others.

This can be confusing and disorienting for others. Your friends or partners might find it difficult to understand why you push them away one minute but seek them out the next, and they might draw the conclusion that you’re doing it on purpose rather than acting on attachment urges. It can be helpful, then, for you and the people in your life to understand what triggers fearful-avoidant attachment styles, what happens when fearful-avoidance is triggered, and how to deal with fearful-avoidant attachment triggers.

What is Fearful Avoidant Attachment?

The fearful-avoidant attachment style is characterized by high attachment avoidance and high attachment anxiety. It’s often confused with disorganized attachment – this is technically a different concept, but they overlap in many ways.

Fearful-avoidant attachment styles typically develop when somebody has an insecure attachment style in childhood combined with later experiences of difficulties in relationships1, 2. It’s a common misconception that trauma must be present for fearful-avoidance to develop, because of the role abuse can (but doesn’t always) play in the disorganized attachment style.

You can read more about fearful-avoidant and disorganized attachment styles via our blog posts on these topics.

What Triggers Someone with Fearful Avoidant Attachment Style?

In psychology, a trigger is something, anything, that causes a person to react. It’s usually used in trauma work to describe events or situations that lead someone to have flashbacks, anxiety attacks, or other symptoms of trauma.

Triggers in this sense lead to an automatic response, meaning you aren’t in control of how you feel or what comes up for you after experiencing a trigger. However, if you’re able to emotionally regulate, you may be able to manage the trigger without feeling like you’re losing control. The good news is that emotional regulation is a practicable skill – we’ll talk more about how to practice emotional regulation and manage attachment triggers soon.

It’s worth keeping in mind that this meaning of the word “trigger” has spread beyond the world of psychology, and you might hear it used in day to day life. The definition is largely the same, except that it’s often applied to a wider range of emotional responses and situations that aren’t necessarily related to trauma or other mental health difficulties. This can make people who experience trauma triggers feel invalidated or stigmatized, so it’s important to understand what we mean by “trigger” and avoid using it to insult, dismiss, or overemphasize emotions.

What Are Attachment Triggers?

In this article, a “trigger” is anything that causes someone with a fearful-avoidant attachment style to experience attachment system activation – whether this is driven by avoidance or anxiety. Although trauma can play a role in developing insecure attachment styles, someone with a fearful-avoidant attachment style doesn’t necessarily have a history of trauma, and their triggers and reactions aren’t necessarily related to a traumatic event.

Because people with fearful-avoidant attachment styles experience conflicting high anxiety and avoidance, their triggers can also be conflicting. Below, we’ve listed 8 of the most common fearful-avoidant triggers:

8 Common Fearful Avoidant Triggers

1. Relationship Conflict

Relationship conflict can be a trigger for anyone with an insecure attachment style – even a small disagreement could activate an anxious or avoidant attachment system. For somebody with a fearful-avoidant attachment style, challenges in relationships can trigger the fear that the relationship will fall apart and lead to attempts to either push their partner away or pull them closer, neither of which are ideal ways to manage disagreements.

2. Relationship Progression

People with high avoidance often report feeling their attachment systems triggered when relationships progress. Even though most people see relationship milestones and commitments as a positive thing, this can be worrying for people with attachment avoidance: the more they invest, the more they have to lose – and they live with the underlying feeling that partners will inevitably let them down.

3. Criticism

It’s never nice to feel criticized or disapproved of by someone you care about, but for people with insecure attachment styles, this feeling could trigger fears that the relationship is at risk. People with fearful-avoidant attachment styles could respond with avoidance or anxiety, though neuropsychological studies using brainwave measurements have suggested that they usually experience avoidance first3.

4. High Emotional Demands

People with fearful-avoidant attachment styles say that high emotional demands from their partner can trigger their attachment avoidance. This can quickly turn into a downward spiral, as the more they withdraw, the more emotional attention their partner might need from them. If their partner eventually withdraws too, the fearful-avoidant partner can experience attachment anxiety in response, resulting in confusion and uncertainty for both partners.

5. Vulnerability

Feeling vulnerable through emotional expression or disclosure can also trigger avoidance in fearful-avoidant partners. In the same way that relationship progression can trigger avoidance, this feeling of vulnerability often comes from the fearful-avoidant partner’s own expectations rather than the partner’s demands.

6. Inconsistency

A partner’s inconsistent behavior can make the future of a relationship feel uncertain, leading fearful-avoidant partners to cycle between withdrawing and “clinging”. We all have different amounts of energy to give to a relationship at any given time, but a pattern of inconsistent behavior might look like regularly switching between caring attentiveness and distance without explanation. The fearful-avoidant partner’s own inconsistent response to this can make the relationship feel even more unstable.

7. Expectations of Secure Behavior

People with fearful-avoidant attachment styles say they struggle with partners’ expectations of secure or “normal” behavior in a relationship. Every relationship comes with its own unique challenges, and insecure attachment styles can influence these challenges in different ways. Someone with a fearful-avoidant attachment style might need more time to process disagreements or milestones, for example, and feeling expectations to behave as though they have a secure attachment style can cause them to withdraw.

8. Feeling Responsible for Others’ Emotions

Again, nobody likes to feel responsible for another person’s emotions – but for someone with high avoidance, this can feel especially suffocating and may trigger attachment avoidance. Fearful-avoidant partners might be more likely to find themselves feeling this way if their partners have insecure attachment styles too; it’s important for both partners to practice emotional regulation and boundary-setting.

Fearful Avoidant and Disorganized Attachment Digital Workbook

If your relationships often take you on an emotional rollercoaster, this book might just be the step you need to take to begin your journey to positive change!

Impact of a Fearful Avoidant Triggers on Relationships

These triggers can make relationships very difficult to navigate, both for people with fearful-avoidant attachment styles and their partners (even if their partners have secure attachment styles).

If you have a fearful-avoidant attachment style and your partner also has an insecure attachment style, you might find that your attachment behaviors trigger each other. For example, if your partner has high avoidance and tends to withdraw, your attachment anxiety can be triggered by this in return, which may lead to even more withdrawal from your partner. In this way, small triggers can become big deals.

It’s important for both partners to take responsibility for their own emotional regulation, boundaries, and contributions to relationship dynamics. At the same time, partnerships involve supporting one another, and partners of people with fearful-avoidant attachment styles often want to know how best to support their partner.

Supporting a Partner with Fearful Avoidant Triggers

First of all, remember that you can’t pour from an empty cup. If you find yourself supporting your fearful-avoidant partner even when you don’t feel you have the capacity to do so, growing resentment and frustration can cause further ruptures in your relationship.

Take time for yourself when needed, and communicate with your partner that you still care about them and your relationship but you need to attend to your own needs.

If you’re the fearful-avoidant partner, try to keep in mind that your partner cannot support you without supporting themselves first. They may not always have the capacity to give you what you need in the moment, and taking space or time to recuperate alone ensures they will have that capacity again later. Even though it can feel like abandonment, try to remember that your partner taking space is usually intended to help preserve the relationship, rather than withdraw from it.

On the other side of the same coin, remember that your partner’s high avoidance means that they may withdraw when they feel relationship pressures weigh on them, whether these pressures stem from conflict or progression. These relationship pressures can make them feel unsafe, and further pressure is likely to make them withdraw even more, while “matching” their withdrawal could trigger their attachment anxiety.

Try to respond to withdrawal with empathy and understanding – let your partner know that you’ll be there when they’re ready, but avoid pushing them to be ready too soon. This can be particularly difficult if you have an insecure attachment style too, and you may need to practice emotional regulation skills to manage your own attachment system.

Alternatively, your partner’s high attachment anxiety might lead them to make extra emotional demands when they feel the relationship is at risk. Again, try to respond with empathy and understanding. You may need to gently set boundaries and remind your partner that this doesn’t mean you love them any differently.

Perhaps the most important thing you can do to support a partner with a fearful-avoidant attachment style is to help them to develop the skills and tools to manage their own attachment triggers. Being open to learning about attachment theory, emotional regulation, and your own relationship dynamic together can help you both to move toward attachment security in the long-term.

Discover Your Attachment Style

If you don’t yet know your attachment style, it’s quick and easy to find out with our free attachment quiz. This quiz will ask you a few questions about your attachment experiences and produce measurements of your attachment anxiety and avoidance. If both are high, this means that you have a fearful-avoidant attachment style.

How to Deal/Manage Fearful Avoidant Triggers

If you have a fearful-avoidant attachment style, don’t worry – there are things you can do to manage your triggers and move closer to attachment security.

We have briefly discussed emotional regulation; this is the ability to recognize and respond to your emotions. Being able to name your emotions is the first step – when you notice a physical sensation, such as your heart racing, pause and try to identify the emotion that caused it. This is easier said than done, and it’s okay if it takes some time to get used to. Mindfulness practice can help with this by teaching us to notice and accept our bodily sensations – in fact, mindfulness has been found to lead to more positive emotional reactions, support emotional regulation, and reduce avoidance4.

Once you’re able to name the emotion, you can use appropriate coping techniques to manage it. Finding helpful coping techniques can involve some trial and error, but lots of people find grounding or soothing activities can help. The process might look like this:

“My heart is racing and my face feels hot… I think I’m feeling anxious. I need validation from my partner, but I know this isn’t a helpful coping technique. I know that box breathing and grounding statements can help when I feel like this, so I’ll try them one at a time.”

Box breathing is a grounding technique that draws your attention to your breath and regulates your breathing. To box breathe, inhale for 4 seconds, hold for 4 seconds, exhale for 4 seconds, and wait 4 seconds before inhaling for another 4 seconds to begin another cycle. You can adapt this in any way that you need to.

Grounding statements are statements you can repeat to yourself aloud, in your head, or even pre-recorded, that help you to feel more present. For example, your grounding statement might be “I am worthy of love and respect. My partner cares about me. Separation does not mean abandonment.”

If you practice grounding or soothing techniques, it’s best to do this when you’re already feeling calm. We learn skills most effectively when emotions aren’t high, so by practicing these techniques before we’re already triggered we can wire our brains to know what to do when the time comes.

When emotions are really high, you can try the “opposite action” method. This is a technique from Dialectical Behavior Therapy in which you do the opposite of what your emotion makes you want to do. For example, if your anger makes you want to say something unkind, the opposite action would be to go out of your way to say something kind instead.

When to Seek Professional Help

If you experience high emotions that get in the way of day to day life or you’re finding emotional regulation really difficult, you may wish to seek professional help from a qualified mental health professional. This could take many different forms – for example, you could try psychoeducation to learn more about the processes that are affecting you and your relationship, or talking therapy to talk through how these processes are showing up for you specifically.

If you do have a history of trauma and symptoms of trauma are impacting your daily life, trauma-focused therapy could incorporate both of these therapeutic methods to help you to feel safe.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), is a specific therapy programme designed to help people with emotional regulation difficulties. It was initially developed for people with borderline personality disorder (BPD), but its lessons are universally helpful (mindfulness, relationship skills, emotional regulation, tolerating distress) and it can be used to treat a range of mental health difficulties.

Conclusion

Having a fearful-avoidant attachment style can be complicated – you don’t want to hurt the people you care about, but your emotional reactions to attachment triggers can be confusing even to you. Learning more about what triggers your attachment system the most, practicing emotional regulation, and communicating openly with your partner can help you to manage your fearful-avoidant attachment triggers and move gradually toward attachment security.

Although it does come with challenges for you and your partner, there is nothing inherently wrong with having a fearful-avoidant attachment style. Attachment styles are influenced by our experiences, especially ones in early life that you could not control. Remember to go forward with self-compassion, and know that by learning more about your attachment style you are already making strides towards a secure attachment style.

TAKE A LOOK AT THE FEARFUL AVOIDANT WORKBOOK

FAQs

Why do I get triggered by both closeness and distance?

If you’re triggered by both closeness and distance in a relationship, you may have a fearful-avoidant attachment style. This is characterized by high attachment anxiety and avoidance, and often develops when we have an insecure attachment style in childhood followed by further relationship difficulties in adolescence and adulthood.

How do I know if I’m making progress with my triggers?

Learning more about your triggers is already progress – being able to identify what specifically triggered you can help you to avoid or pre-empt the trigger next time. Learning how to manage your emotional response to these triggers takes time and patience, but if you keep practicing helpful coping mechanisms you’ll find that triggers gradually become easier to manage.

Is being triggered always related to past trauma?

“Triggered” in the psychological sense usually refers to trauma, but the commonly understood definition of what it means to be triggered has changed as the term has become popular in daily life. Having a strong emotional reaction to something isn’t usually related to trauma, and might be entirely expected depending on the context – but if you experience other symptoms of PTSD or acute trauma, then “being triggered” might be related to past trauma.

References

1. Taunton M, McGrath L, Broberg C, Levy S, Kovacs AH, Khan A. Adverse childhood experience, attachment style, and quality of life in adult congenital heart disease. International Journal of Cardiology Congenital Heart Disease. 2021 Oct 1;5:100217.

2. van Bussel EM, Wierdsma AI, van Aken BC, Willems IE, Mulder CL. The Associations between Attachment, Adverse Childhood Experiences and Re-Victimization in Patients with a Psychosis Spectrum Disorder. Medical Research Archives. 2024 Jul 31;12(7).

3. Dan O, Zreik G, Raz S. The relationship between individuals with fearful-avoidant adult attachment orientation and early neural responses to emotional content: An event-related potentials (ERPs) study. Neuropsychology. 2020 Feb;34(2):155.

4. Roemer L, Williston SK, Rollins LG. Mindfulness and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015 Jun 1;3:52-7.

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox

Get mental health tips straight to your inbox